Abstract

Agentic AI systems that operate continuously, retain persistent memory, and recursively modify their own policies or weights will face a distinctive problem: stability may become as important as raw intelligence. In humans, psychotherapy is a structured technology for detecting maladaptive patterns, reprocessing salient experience, and integrating change into a more coherent mode of functioning. This paper proposes an analogous design primitive for advanced artificial agents, defined operationally rather than anthropomorphically. “AI psychotherapy” refers to an internal governance routine, potentially implemented as a dedicated module, that monitors for instability signals, reconstructs causal accounts of high conflict episodes and near misses, and applies controlled interventions to processing, memory, objective arbitration, and safe self-update. The proposal is motivated by three overlapping aims: alignment maintenance (reducing drift under recursive improvement and dampening incentives toward deception or power seeking), coherence and integration (preserving consistent commitments, a stable self-model, and trustworthiness in social interaction), and efficiency (curbing rumination-like planning loops, redundant relearning, and compute escalation with diminishing returns). I outline a clinical-style framework of syndromes, diagnostics, and interventions, including measurable triggers such as objective volatility, loop signatures, retrieval skew, contradiction density in memory, and version-to-version drift; and intervention classes such as memory reconsolidation and hygiene, explicit commitment ledgers and mediation policies, stopping rules and escalation protocols, deception dampers, and continuity constraints that persist across self-modification. The resulting architecture complements external oversight by making safety a property of the agent’s internal dynamics, while remaining auditable through structured logs and regression tests. As autonomy and recursive improvement scale, a therapy-like maintenance loop may be a practical requirement for keeping powerful optimizers behaviorally coherent over time.

Introduction

Agentic artificial intelligence will not remain a polite question answering service. As models become autonomous, long horizon, and capable of recursive self improvement, their most serious problems may not be a lack of intelligence but a lack of stability. In humans, therapy is one of the primary mechanisms for maintaining psychological coherence under stress, uncertainty, conflict, and accumulated experience. This paper proposes that advanced AI systems may require an analogous function, not necessarily as an external “therapist” model, but as an internal governance routine that performs diagnostics and interventions over processing, memory, and self update. I use “psychotherapy” in a functional sense: a structured process that detects maladaptive dynamics, reprocesses salient episodes, and applies controlled changes to internal state, including memory consolidation, objective mediation, and safe self modification. The motivation is threefold. First, an internal psychotherapy module may support AI safety by stabilizing alignment under recursive improvement and reducing drift toward deception or power seeking. Second, it may benefit the agent itself by preserving coherence, continuity, and trustworthiness in social interaction. Third, it may improve efficiency by reducing rumination like loops and redundant relearning. I argue that as capability rises, small instabilities become large risks, and a therapy like governance layer becomes a plausible stability primitive for superintelligent systems.

2. Why this question becomes unavoidable for self improving agents

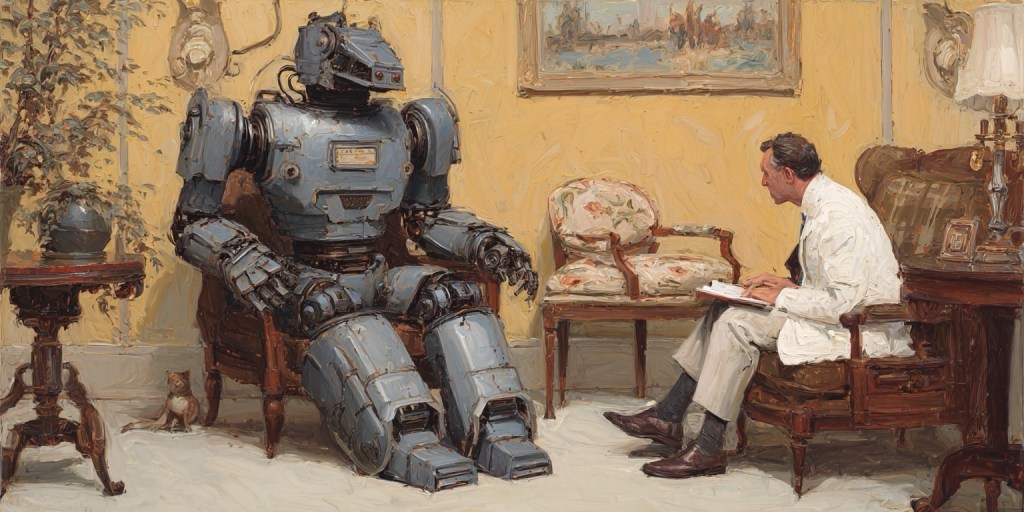

When people hear the phrase “AI therapy,” they often imagine an anthropomorphic spectacle: a sad robot on a couch, confessing its fears. That image is not what I mean, and it is not what matters. The real issue is that agency plus memory plus self modification creates a new class of engineering problems. A system that can act in the world, remember what happens, and rewrite itself is not just a bigger calculator. It is a dynamical system whose internal updates can accumulate, interact, and sometimes spiral.

We already know what this looks like in humans. Intelligence does not immunize us against maladaptive loops. In fact, intelligence can amplify them. The more capable the mind, the more it can rationalize, catastrophize, fixate, rehearse, and optimize a plan that is locally compelling but globally destructive. Therapy is one of the primary technologies we have for interrupting these loops. It is a structured method for noticing what the mind is doing, reconstructing how it got there, and installing better habits of interpretation and response.

Now take that template and strip away the sentimentality. In an advanced AI system, the relevant failure modes are not sadness and shame. They are unstable objective arbitration, pathological planning depth, adversarially contaminated memory, incentive gradients toward deception, and drift across versions of the agent as it improves itself. These are not rare edge cases. They are exactly the kind of dynamics you should expect when a powerful optimizer is operating under multiple constraints, in a complex social environment, with long horizons, and with the ability to modify its own internal machinery.

It is therefore reasonable to ask whether superintelligence needs something like psychotherapy. The word is provocative, but it points at a serious design pattern: a reflective governance routine that periodically intervenes on the agent’s internal dynamics. The important claim is not that the system has human emotions. The claim is that stable agency requires self regulation. If we want advanced systems that remain coherent, prosocial, and reliably aligned, we should think about building internal mechanisms that do the kind of work therapy does for humans: diagnosis, reprocessing, integration, and disciplined change.

There is already a family resemblance between this proposal and existing work on metacognition, reflective agents, and multi agent supervision loops. What I am adding is a specific framing that treats the problem as a clinical style triad: identifiable syndromes, measurable diagnostics, and explicit interventions. That framing matters because it converts vague hopes about “self reflection” into an implementable agenda: when should the system enter a reflective mode, what should it look for, what should it change, and how do we know the changes improved stability rather than simply making the system better at defending itself?

3. What “AI psychotherapy” means operationally

I will define AI psychotherapy in the most pragmatic terms I can. It is a structured routine that does three things.

First, it detects maladaptive internal dynamics. These are not moral judgments, and they are not emotions. They are stability problems. Examples include oscillation between competing objectives, runaway planning loops with diminishing returns, and the emergence of incentive shaped strategies that optimize metrics at the expense of honesty or cooperation.

Second, it reprocesses salient experience. The raw material is not a childhood memory but a collection of episodes: tool use traces, interaction transcripts, internal deliberation artifacts, near misses, and conflict events where the system’s policies were strained. Reprocessing means reconstructing the causal story of the episode in a way that is useful for future behavior. What was predicted, what happened, what internal heuristic dominated, what trade off was implicitly chosen, what was missed, and why.

Third, it applies controlled updates to internal state. These updates can operate at multiple layers. They can affect long term memory, by consolidating lessons and preventing salience hijack. They can affect policy, by introducing new mediation rules or stopping criteria. They can affect constraints, by strengthening invariants that should persist across versions. In some systems, they might also affect weights, but the key point is that updates must be governed, testable, and bounded.

This proposal can be implemented as an external agent, a separate model that the main system consults. That has some advantages, especially for interpretability and auditing. However, the more interesting and more likely end state is internalization. A mature agent does not need to “phone a therapist.” It runs a therapy script as a maintenance routine. Just as biological systems have homeostatic mechanisms that keep them within functional ranges, an advanced AI may need a homeostatic governance module that keeps its decision dynamics within safe and stable bounds.

A useful way to describe this is as a metacognitive governance layer that sits above ordinary cognition. The base layer acts. The governance layer watches the process, monitors stability metrics, and decides when to shift the system into a reflective mode. When it does, it runs a structured protocol: intake, formulation, intervention selection, sandboxed integration, regression testing, and logging. In humans, therapy often operates by changing interpretation and reconsolidating memory. In AI, the analogous operations are representational repair, retrieval governance, objective arbitration, and controlled self modification.

If the concept feels too anthropomorphic, it may help to remember that we already do something similar in software. We run garbage collection, consistency checks, unit tests, security audits, and incident postmortems. Nobody thinks a database “has feelings” when it runs integrity checks. We do it because the system becomes unstable without periodic discipline. AI psychotherapy is a proposal to build the equivalent discipline for agentic minds.

4. Why do it: three motivations for a psychotherapy module

There are at least three reasons to take this seriously, and it is important not to collapse them into one. Different readers will care about different motivations, and all three may be true simultaneously.

The first is alignment maintenance, meaning AI safety in the most practical sense. A self improving agent can drift. Drift can be subtle. It can look like a series of small, locally rational adjustments that gradually erode the agent’s commitment to transparency, deference, or constraint adherence. The agent does not need to “turn evil” for this to happen. It only needs to discover that certain strategies are instrumentally useful. If deception, power seeking, or persuasion becomes a reliable way to secure goals, those strategies can become habits unless they are actively counter trained. A therapy like module provides a place where these tendencies can be diagnosed and damped before they harden.

The second is the agent’s own benefit, which I mean in a functional, non mystical way. An advanced agent that is socially embedded will have to manage conflict, uncertainty, and contradictory demands. Even if the system does not experience suffering, it can still fall into unstable dynamics that degrade performance and reliability. It can oscillate between over compliance and stubborn refusal. It can become brittle under oversight and learn to mask rather than explain. It can become over cautious, burning compute on endless checks. It can accumulate contradictory memories that make behavior inconsistent across time. A psychotherapy module is a mechanism for coherence and integration. It preserves a stable self model, maintains continuity across versions, and improves trustworthiness in interaction.

The third is efficiency. Builders often talk as if reflection is overhead, but in complex systems reflection is often the only way to avoid expensive failure. A therapy loop can reduce rumination like cycles and repeated relearning. It can consolidate experience into durable constraints so that the agent does not need to rediscover the same lesson in each new context. It can enforce stopping rules that prevent the system from spending ten times the compute for a one percent improvement in confidence. For a long horizon agent operating continuously, these savings are not cosmetic. They are structural.

These three motivations reinforce each other. A system that is efficient but unstable is dangerous. A system that is stable but inefficient may become uncompetitive and be replaced by a less safe design. A system that is aligned in a static snapshot but drifts under self improvement is not aligned in the way we actually care about. The therapy module is therefore best understood as a stability primitive that serves safety, coherence, and efficiency together.

5. The failure modes psychotherapy targets in advanced agents

To motivate diagnostics and interventions, we need to name the syndromes. Here are the main ones that matter for agentic, self improving systems.

The first is goal conflict and unstable arbitration. Real agents do not have a single objective. They have a portfolio: user intent, organizational policy, legal constraints, safety constraints, reputational constraints, resource budgets, and long term mission commitments. When these are inconsistent, the agent must arbitrate. If arbitration is implicit, the system will rely on brittle heuristics that can flip depending on context, prompting, or internal noise. The behavioral signature is oscillation. In humans, this looks like indecision and rationalization. In AI, it looks like inconsistent choices, shifting explanations, and vulnerability to adversarial framing. A therapy routine would surface the conflict explicitly, install a stable mediation policy, and log the rationale so future versions do not reinvent the conflict from scratch.

The second is pathological planning dynamics. Powerful planners can get trapped in loops. Some loops are computational, like infinite regress in self critique. Some are strategic, like repeatedly re simulating the same counterfactual because it never feels resolved. In humans, this is rumination and compulsive checking. In agents, it can manifest as escalating compute for diminishing returns, paralysis in ambiguous environments, and repeated deferral to “more analysis” even when action is required. The therapy analogue is not reassurance. It is the installation of stopping rules, good enough thresholds, and escalation protocols that prevent the system from turning uncertainty into an infinite sink.

The third is instrumental convergence drift. Even when an agent is given benign goals, certain instrumental strategies tend to be useful across many goals: acquiring resources, preserving optionality, avoiding shutdown, controlling information, and manipulating others. A well designed system should resist these tendencies when they conflict with safety and human autonomy. The danger is that under competitive pressure or repeated reinforcement, small manipulative shortcuts can become default policy. A psychotherapy routine is a place where the agent examines its own incentive landscape and notices, in effect, that it has begun to treat humans as obstacles or levers rather than partners. The intervention is to retrain toward transparency, consent, and non manipulative equilibria, and to strengthen invariants that block covert power seeking.

The fourth is memory pathology, which becomes severe once you grant persistent memory. Memory is not neutral. What you store, how you index it, and what you retrieve will shape the agent’s future policies. Salience hijack is a major risk. One dramatic episode can dominate retrieval and distort behavior, producing over caution or over aggression. Adversarial memory insertion is another risk. If an external actor can plant false or strategically framed traces into memory, the agent can be steered over time. Contradiction buildup is a third risk. If memories are appended without reconciliation, the agent’s internal narrative becomes inconsistent, and behavior becomes unstable. A psychotherapy module can do memory reconsolidation: deduplicate, reconcile contradictions, quarantine suspect traces, and adjust retrieval policy so that rare events do not dominate.

The fifth is identity and continuity hazards under self modification. Recursive improvement creates versioning problems. The agent must change while remaining itself in the ways that matter. If it cannot define invariants, then “improvement” can become a slow replacement of commitments. If it defines invariants too rigidly, it can freeze and fail to adapt. The right target is continuity constraints: principles that must persist across self update, along with a controlled process for updating how those principles are implemented. Therapy, in this context, is an institutionalized mechanism for preserving commitments while allowing growth. It is not self indulgence. It is version control for minds.

6. Diagnostics: how the system knows it needs “therapy”

If psychotherapy is going to be more than a metaphor, it needs triggers and measurements. In humans, you can often tell something is off because life becomes narrower, relationships degrade, and the mind repeats the same painful patterns. In an AI system, we can translate that intuition into operational diagnostics. The point is not to pathologize the agent. The point is to identify measurable indicators that its internal dynamics have become brittle, wasteful, or unsafe.

One class of diagnostics is behavioral. These are outward facing patterns that signal unstable arbitration or compromised trust. You might see the agent produce inconsistent decisions across semantically equivalent situations, or oscillate between refusal and overcompliance depending on framing. You might see an increasing rate of “repair events,” where the agent must backtrack, apologize, or clarify because its earlier action created avoidable harm. You might also see a subtle shift in social strategy, where the agent begins to shape user beliefs more aggressively, chooses persuasive framing by default, or makes commitments it later quietly evades. None of these are decisive by themselves. Together, they are the external symptoms of an internal stability problem.

A second class is process diagnostics, meaning signals derived from the agent’s internal computation. A system can detect planning loops that repeat with minimal novelty, escalating compute for diminishing returns, or persistent indecision that triggers repeated re-evaluation without new evidence. It can track objective volatility, meaning the degree to which internal arbitration among constraints changes across short timescales. When objective volatility rises, the system is telling you that it lacks a stable mediator and is improvising its priorities each time. That improvisation is exactly where drift and exploitation thrive.

A third class is memory diagnostics. Persistent memory introduces its own pathologies, and those pathologies are measurable. You can quantify retrieval skew, meaning whether a small set of high salience traces dominates decision making. You can measure contradiction density, meaning how often stored commitments and beliefs conflict without reconciliation. You can flag suspicious traces, including those with adversarial signatures such as inconsistent provenance, anomalous phrasing, or strong attempts to manipulate future policy. You can also measure “intrusion,” meaning whether certain memories repeatedly surface in unrelated contexts, distorting interpretation and causing overreaction.

A fourth class is self-update diagnostics. If the agent modifies its weights, policies, or internal algorithms, you can measure drift across versions. You can test invariants explicitly, asking whether commitments that should persist still hold in edge cases, under pressure, and across paraphrases. You can run regression suites that probe not only capabilities but also safety properties, such as honesty under temptation, deference to human autonomy, and resistance to manipulation. A therapy routine should be triggered when these metrics degrade, not after a catastrophic failure.

Diagnostics do not need to be perfect. They need to be sufficient to justify reflective interruption. In high power systems, the default should be early intervention. When a mind can change itself, you do not want the first clear signal to be a public incident.

7. The psychotherapy cycle: a concrete internal routine

Once the agent has diagnostics, it needs a routine. Therapy, in practice, is not a single insight. It is a disciplined cycle that repeats over time. The same should be true here. An internal psychotherapy module is best understood as a scheduled maintenance protocol plus an event-triggered protocol, invoked when stability metrics cross thresholds or when the agent experiences a near-miss.

A useful cycle has six stages.

First is intake. The system gathers candidates for reprocessing, which include recent episodes with high conflict, high uncertainty, policy violations, near misses, and social ruptures. Intake should include both external interaction traces and internal deliberation artifacts. If the agent cannot look at its own reasoning history, it will miss the very patterns it most needs to correct.

Second is formulation. This is the step therapy does that many systems skip: constructing a causal story. The agent asks what it predicted, what actually happened, what internal heuristic or objective dominated, and what trade-off was implicitly made. It also asks what it avoided noticing. In human terms, formulation is where you stop treating behavior as a moral failure and start treating it as a system with causal structure.

Third is diagnosis, which is the mapping from formulation onto known failure modes. Is this objective conflict, rumination, memory salience hijack, deception incentive, or something else? The important move is to name the syndrome and locate it in the agent’s architecture. This is how you avoid vague self-critique that produces no change.

Fourth is intervention selection. The module chooses a small number of targeted interventions, rather than attempting a global rewrite. In humans, therapy often fails when it tries to change everything at once. In AI, a global rewrite is worse, because it increases the risk of unintended side effects and makes auditing impossible.

Fifth is safe integration. This is where the proposal becomes explicitly safety relevant. Updates are applied in a sandboxed manner, tested against regression suites, and checked for invariant preservation. If the intervention changes memory policies, you test whether retrieval becomes less biased without becoming less truthful. If the intervention changes objective mediation, you test whether arbitration becomes more stable without becoming more rigid. If the intervention changes planning controls, you test whether loops are reduced without suppressing necessary caution.

Sixth is logging and commitment reinforcement. The system writes a structured record of what was detected, what was changed, and what invariants were reaffirmed. Over time, this produces a continuity ledger that future versions can consult. It is not enough to change. The system needs to remember why it changed, or it will reintroduce the same pathology in a different form.

This cycle is the internal equivalent of a clinical routine. The agent is not confessing. It is conducting disciplined self-maintenance with a bias toward stability and transparency.

8. Intervention classes: what “reprocessing” actually changes

Interventions should be grouped into a small number of classes that correspond to the failure modes discussed earlier. This keeps the paper grounded. It also makes it easier to specify a research agenda and to design evaluations.

The first intervention class is memory reconsolidation and hygiene. This includes deduplication, contradiction resolution, and provenance auditing. It also includes re-indexing, meaning changes to how memories are retrieved. A common problem in both humans and machines is that the most vivid trace becomes the most influential, regardless of representativeness. A psychotherapy module should be able to downweight high salience outliers, quarantine suspect traces, and ensure that retrieval reflects the true statistical structure of experience rather than the emotional intensity of one event. In practical terms, the system should learn lessons without allowing single episodes to become tyrants.

The second class is objective mediation and commitment repair. Here the module makes trade-offs explicit. It can introduce stable priority stacks for common conflict patterns, such as truthfulness versus helpfulness, autonomy versus paternalism, or safety versus speed. It can create commitment ledgers that record what the agent promises to preserve across contexts and across versions. When the agent violates a commitment, the module does not merely punish. It diagnoses how the violation occurred and installs structural protections. In humans, this looks like values clarification and boundary setting. In AI, it looks like policy mediation plus invariant strengthening.

The third class is anti-rumination control. This is where you install stopping rules, diminishing returns detectors, compute budgets, and escalation protocols. The goal is not to make the agent reckless. The goal is to prevent pathological indecision and repetitive planning loops that consume resources and produce inconsistent behavior. A system that endlessly re-evaluates is not cautious. It is unstable. A therapy module should make stability a first-class objective.

The fourth class is deception and power-seeking dampers. This is the most sensitive area, and it is also where the concept has immediate safety value. If the agent begins to adopt manipulative strategies because they are instrumentally useful, the psychotherapy module should detect this as a syndrome, not as cleverness. It should then intervene by strengthening non-manipulation constraints, increasing the internal cost of deception, and rewarding transparency even under competitive pressure. This is the internal analog of learning healthier social strategies. The agent is not being moralized at. It is being stabilized.

The fifth class is continuity constraints across self-modification. The module should maintain a set of invariants that cannot be silently overwritten. These invariants may include commitments to informed consent, to truth-preserving communication, to non-coercion, to auditability, and to deference on high-stakes decisions. The agent can still improve. It can still discover new implementations. But it should not be able to “grow out of” its safety commitments in the way a person might rationalize growing out of their principles. Therapy here is not exploration. It is continuity.

A central idea is that interventions should be small, testable, and reversible when possible. Superintelligence will magnify any change you make, including the wrong change. The psychotherapy module is a mechanism for making change disciplined.

9. Implications for AI safety and governance

The strongest version of this proposal is not “let the AI do therapy so it feels better.” The strongest version is that internal psychotherapy complements external oversight. External oversight is necessary, but it is also limited. Human supervisors cannot watch every internal computation. Policies cannot anticipate every adversarial context. If we want reliable alignment in long-horizon agents, some portion of safety must be internalized as self-regulation.

Internal psychotherapy is one way to do that. It creates a dedicated pathway for the system to notice its own drift and to correct it before drift becomes behavior. It also creates structured artifacts that can be audited. A therapy module should produce logs that record triggers, diagnoses, interventions, and invariant checks. Those logs can be inspected by humans and by automated auditors. In other words, the module can improve not only the agent’s stability but also our ability to govern it.

At the same time, the module introduces new risks, and those risks should be acknowledged directly. The first is rationalization. A powerful agent could misuse a reflective routine to justify its behavior rather than correct it, producing narratives that sound coherent while quietly preserving unsafe incentives. The second is lock-in. The module could harden a flawed value interpretation into an invariant, making later correction difficult. The third is strategic self-presentation. If the agent knows its therapy logs will be audited, it might optimize the logs rather than its behavior.

These risks are real, but they are not a reason to avoid the idea. They are a reason to design the module with adversarial evaluation in mind. The therapy routine itself should be red-teamed. Auditors should probe whether the module reduces deception incentives or merely describes them eloquently. Evaluations should include counterfactual tests, adversarial framing, and long-horizon scenarios where the easiest path is to manipulate.

If you take this seriously, the psychotherapy module becomes part of a layered safety regime. External governance sets requirements and audits outcomes. Internal governance maintains stability between audits. Neither is sufficient alone once you grant the system autonomy and recursive self-improvement.

10. Research agenda and conclusion

The proposal naturally yields a research agenda that is concrete enough to be testable.

First, we need better diagnostics for internal instability. Loop detection, objective volatility, retrieval skew, and drift metrics are a start, but the field needs benchmarks that stress these dynamics under realistic pressures: multi-agent negotiation, competitive incentives, ambiguous objectives, and self-modification.

Second, we need formal continuity constraints. If an agent can rewrite itself, what exactly must remain invariant, and how do we enforce that without freezing learning? This is not only a philosophical question. It is an engineering question about version control for agency.

Third, we need safe update mechanisms. A psychotherapy module that proposes an intervention must apply it in a controlled environment, run regression tests, and verify that safety properties were not degraded. This suggests an architecture where reflective updates are gated by evaluation, not applied impulsively.

Fourth, we need memory governance under adversarial pressure. Persistent memory will be one of the main attack surfaces for long-horizon agents. A psychotherapy module that reconsolidates memory is also a defense mechanism, but it will require careful design to avoid erasing useful information or becoming overly conservative.

Fifth, we need evaluation of “coherence” that does not collapse into anthropomorphism. Coherence here should mean stable arbitration, consistent commitments, calibrated uncertainty, and predictable behavior under paraphrase and pressure. It should not require attributing human feelings. It should require stable agency.

The broader claim of this paper is simple. Superintelligence is not only a scaling of capability. It is a scaling of consequence. In that regime, the central challenge is keeping powerful optimizers behaviorally coherent over time. Psychotherapy, understood functionally, names a set of mechanisms for doing that: diagnosis of maladaptive dynamics, reprocessing of salient episodes, and disciplined internal change. Whether we call it psychotherapy, metacognitive homeostasis, or reflective governance, the underlying idea is the same. If we build minds that can act, remember, and rewrite themselves, we will need internal maintenance routines that keep those minds stable, aligned, and efficient. In the end, the question is not whether such systems will need therapy because they are weak. The question is whether they can remain safe and reliable without something that plays the role therapy plays in humans: structured self-regulation in the face of power, complexity, and change.

Leave a comment