Thesis:

Writing with the use of AI should be more broadly, accepted, because it improves clarity, throughput, and ergonomics, but it must come with norms for human accountability, verification, and transparent process, especially as detection and provenance evolve.

1. The hidden cost of “traditional writing”

I love writing, but I do not love what writing does to the body.

To write the old way, you sit. You sit still. You lean forward a little. Your shoulders creep up. Your hands clamp around a keyboard for hours. Your eyes narrow. Your mind tightens into a single point. And you tell yourself this is the price of producing something good.

Over time, it adds up. It is not just the time. It is the strain. It is the posture. It is the repetitive motion. It is the way concentration can become a kind of bodily lock.

There is also something subtle that most people do when they are intensely focused at a screen. They breathe shallowly. Sometimes they almost stop breathing. I call it concentration apnea. You are not trying to do it. It just happens. It is like your nervous system quietly decides that breathing is optional while you wrestle with a paragraph.

So here is the uncomfortable question. If we now have a tool that can help us craft sentences, organize thoughts, and create readable drafts faster, and if using it reduces the hours of locked posture and shallow breathing, why would we treat that as morally suspect? Why would we preserve suffering as a requirement for authorship?

I am not saying writing should become effortless. Thinking is not effortless. Originality is not effortless. Honesty is not effortless. But the physical grind of sentence sculpting, especially when it becomes an all day ordeal, is not some sacred ritual. It is just friction. If we can reduce that friction without sacrificing truth, voice, or responsibility, that is progress.

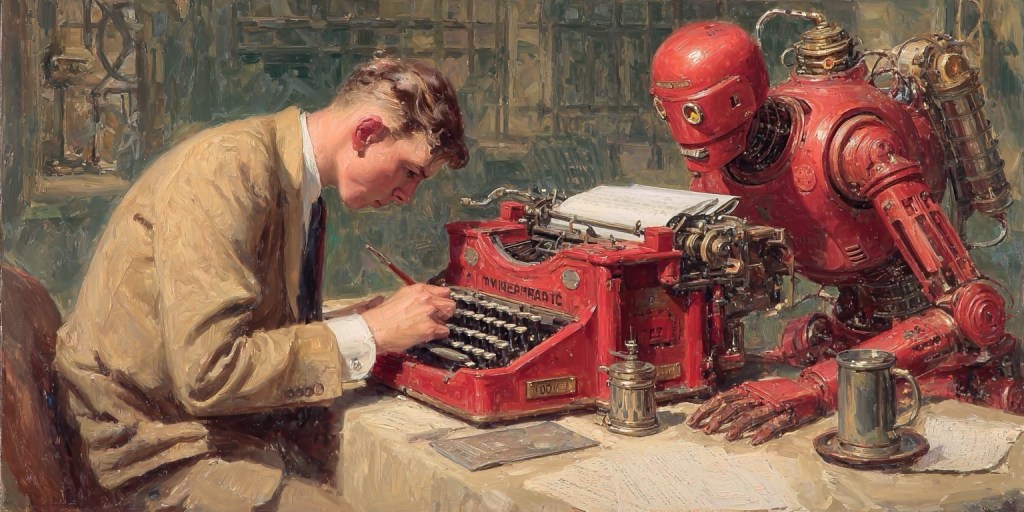

2. What I mean by CENTAUR writing

I am calling this CENTAUR writing.

The basic idea is simple. The best writer right now is often not a human alone and not a machine alone. It is the combination.

A CENTAUR workflow looks like this:

A human has the thesis. The human decides what the piece is really trying to say. The human supplies the lived experience, the intellectual taste, the ethical boundaries, and the willingness to stand behind claims. The machine helps with the heavy lifting of language. It drafts. It offers alternate phrasings. It reorganizes. It smooths transitions. It expands a sketch into a readable section. It compresses a messy section into something tight. The human edits. The human verifies. The human removes fluff. The human restores voice. The human decides what stays and what goes. The human remains accountable.

That is the important part. CENTAUR writing is not outsourcing your mind. It is using a tool to reduce the cost of expressing what your mind is doing.

This is also not “press button, receive content.” That is not writing. That is content generation. It is a different activity with a different purpose. CENTAUR writing still requires a human to direct the process because chatbots cannot reliably prompt themselves into good work, and they cannot take responsibility for what they output. A chatbot can be fluent and wrong. A human has to be the adult in the room.

3. Why writing feels different than programming

People already accept AI assistance in programming. In many circles, it is normal. Nobody gasps when a developer uses autocomplete or a code model. In fact, it is seen as smart.

So why does writing trigger a different reaction?

Part of it is cultural. We romanticize writing. We treat it like a direct window into the soul. We attach identity to sentences.

But there is also a practical reason. In programming, mistakes often reveal themselves quickly. Code runs or it does not. Tests pass or they do not. A compiler is brutally honest. You get immediate feedback.

Writing does not have that. A paragraph can be beautifully written and completely false. A confident tone can hide weak logic. A smooth explanation can quietly drop an important qualifier. In writing, the output can feel correct without being correct.

So people worry, and some of that worry is legitimate. If you treat a chatbot as a truth engine, you will publish errors. If you treat it as a mind replacement, you will drift into genericness. If you treat it as a shortcut to credibility, you will create polished nonsense.

But none of that implies we should ban the tool or treat it as shameful. It implies we need stronger norms.

In other words, the difference between programming and writing is not that writing is sacred. The difference is that writing requires more human judgment at the point of publication. Writing is easier to fake, easier to smooth over, and easier to inflate with plausible filler.

So the real question is not “should we use AI to write?” The real question is “what standards should we adopt so that AI assisted writing is responsible, readable, and worth the reader’s time?”

4. The benefits, and why they are not trivial

If you use a chatbot well, the benefits are not small. They are structural.

First, speed and throughput. You can write more essays. You can actually finish the things you meant to write. You can turn notes into an organized piece in a single sitting, not a week of starts and stops.

Second, readability. A chatbot can take a rough argument and help shape it into something coherent. It can fix the part where your brain jumped three steps and forgot the reader is not inside your head. It can offer alternate ways of saying the same thing until the sentence finally lands.

Third, iteration. You can generate three versions of the intro and pick the best one. You can try a more formal tone, then a more personal tone, then a sharper tone, and see what fits. You can expand a paragraph into a full section, then compress it back down to its essentials.

Fourth, access. If you are not a confident writer, if you are not a native speaker, if you have limited time, if you are dealing with fatigue, a tool that helps you express yourself can be empowering. It lets more people participate in writing as a public act.

Fifth, the health and ergonomics angle. For me, this matters. Writing the old way can turn into hours of sitting, typing, and narrowing attention until the body feels like it has been held in a clamp. Using AI assistance can shift the work from “microcraft every sentence” to “direct, review, and refine.” That often means less keyboard time, less strain, and less of that shallow breathing loop where your body forgets to breathe because your mind is trying to perfect a paragraph.

There is also a psychological benefit that is hard to quantify. When the “blank page” is no longer a wall, you show up more consistently. You are less likely to procrastinate. You do not need a perfect burst of inspiration to begin. You can begin by conversing, and then shape the conversation into prose.

That does not make the writing less human. It makes the writing more possible.

5. The costs, and the real ways this can go wrong

The downside is also real, and if we normalize CENTAUR writing, we should say the risks out loud.

The first risk is hallucination, meaning the chatbot states something as fact that is not true. This is not rare. It can be subtle. It can be a date that is off. It can be an invented citation. It can be a confident summary of a paper it never actually read. If you publish without verification, you will eventually publish errors.

The second risk is what I call polished mediocrity. The chatbot is very good at producing paragraphs that sound like an essay. It is good at “essay voice.” The danger is that you end up with text that feels substantial but is not. It is smooth, generic, and forgettable. It can become AI slop. Not because the tool is evil, but because the workflow did not force specificity and thinking.

The third risk is homogenization. If many people lean on the same kind of assistant, writing can converge. You start seeing the same rhetorical moves, the same transitions, the same safe conclusions. Even if the writing improves locally, culture can become flatter globally. If you care about voice and originality, you have to actively protect them.

The fourth risk is skill atrophy. If you never struggle with phrasing, you may lose some of your own ability to do it. More importantly, if you let the chatbot do your thinking, you will get weaker as a thinker. The tool should relieve the cost of expression, not replace the act of forming a view.

The fifth risk is privacy and confidentiality. People paste everything into chats. Drafts. Personal stories. Work documents. Sensitive material. If we normalize CENTAUR writing, we also need to normalize boundaries. Not everything belongs in a prompt.

The sixth risk is trust. Readers want to know who is speaking. They want to know whether the author actually means what is written. If AI assistance becomes common and undisclosed in contexts where disclosure matters, trust can erode. And once trust erodes, everyone pays the price, including careful writers.

So yes, CENTAUR writing is an advantage. But it is not a free lunch. It is a tool that increases power. When power increases, responsibility has to increase with it.

1. The hidden cost of “traditional writing”

I love writing, but I do not love what writing does to the body.

To write the old way, you sit. You sit still. You lean forward a little. Your shoulders creep up. Your hands clamp around a keyboard for hours. Your eyes narrow. Your mind tightens into a single point. And you tell yourself this is the price of producing something good.

Over time, it adds up. It is not just the time. It is the strain. It is the posture. It is the repetitive motion. It is the way concentration can become a kind of bodily lock.

There is also something subtle that most people do when they are intensely focused at a screen. They breathe shallowly. Sometimes they almost stop breathing. I call it concentration apnea. You are not trying to do it. It just happens. It is like your nervous system quietly decides that breathing is optional while you wrestle with a paragraph.

So here is the uncomfortable question. If we now have a tool that can help us craft sentences, organize thoughts, and create readable drafts faster, and if using it reduces the hours of locked posture and shallow breathing, why would we treat that as morally suspect? Why would we preserve suffering as a requirement for authorship?

I am not saying writing should become effortless. Thinking is not effortless. Originality is not effortless. Honesty is not effortless. But the physical grind of sentence sculpting, especially when it becomes an all day ordeal, is not some sacred ritual. It is just friction. If we can reduce that friction without sacrificing truth, voice, or responsibility, that is progress.

2. What I mean by CENTAUR writing

I am calling this CENTAUR writing.

The basic idea is simple. The best writer right now is often not a human alone and not a machine alone. It is the combination.

A CENTAUR workflow looks like this:

A human has the thesis. The human decides what the piece is really trying to say. The human supplies the lived experience, the intellectual taste, the ethical boundaries, and the willingness to stand behind claims. The machine helps with the heavy lifting of language. It drafts. It offers alternate phrasings. It reorganizes. It smooths transitions. It expands a sketch into a readable section. It compresses a messy section into something tight. The human edits. The human verifies. The human removes fluff. The human restores voice. The human decides what stays and what goes. The human remains accountable.

That is the important part. CENTAUR writing is not outsourcing your mind. It is using a tool to reduce the cost of expressing what your mind is doing.

This is also not “press button, receive content.” That is not writing. That is content generation. It is a different activity with a different purpose. CENTAUR writing still requires a human to direct the process because chatbots cannot reliably prompt themselves into good work, and they cannot take responsibility for what they output. A chatbot can be fluent and wrong. A human has to be the adult in the room.

3. Why writing feels different than programming

People already accept AI assistance in programming. In many circles, it is normal. Nobody gasps when a developer uses autocomplete or a code model. In fact, it is seen as smart.

So why does writing trigger a different reaction?

Part of it is cultural. We romanticize writing. We treat it like a direct window into the soul. We attach identity to sentences.

But there is also a practical reason. In programming, mistakes often reveal themselves quickly. Code runs or it does not. Tests pass or they do not. A compiler is brutally honest. You get immediate feedback.

Writing does not have that. A paragraph can be beautifully written and completely false. A confident tone can hide weak logic. A smooth explanation can quietly drop an important qualifier. In writing, the output can feel correct without being correct.

So people worry, and some of that worry is legitimate. If you treat a chatbot as a truth engine, you will publish errors. If you treat it as a mind replacement, you will drift into genericness. If you treat it as a shortcut to credibility, you will create polished nonsense.

But none of that implies we should ban the tool or treat it as shameful. It implies we need stronger norms.

In other words, the difference between programming and writing is not that writing is sacred. The difference is that writing requires more human judgment at the point of publication. Writing is easier to fake, easier to smooth over, and easier to inflate with plausible filler.

So the real question is not “should we use AI to write?” The real question is “what standards should we adopt so that AI assisted writing is responsible, readable, and worth the reader’s time?”

4. The benefits, and why they are not trivial

If you use a chatbot well, the benefits are not small. They are structural.

First, speed and throughput. You can write more essays. You can actually finish the things you meant to write. You can turn notes into an organized piece in a single sitting, not a week of starts and stops.

Second, readability. A chatbot can take a rough argument and help shape it into something coherent. It can fix the part where your brain jumped three steps and forgot the reader is not inside your head. It can offer alternate ways of saying the same thing until the sentence finally lands.

Third, iteration. You can generate three versions of the intro and pick the best one. You can try a more formal tone, then a more personal tone, then a sharper tone, and see what fits. You can expand a paragraph into a full section, then compress it back down to its essentials.

Fourth, access. If you are not a confident writer, if you are not a native speaker, if you have limited time, if you are dealing with fatigue, a tool that helps you express yourself can be empowering. It lets more people participate in writing as a public act.

Fifth, the health and ergonomics angle. For me, this matters. Writing the old way can turn into hours of sitting, typing, and narrowing attention until the body feels like it has been held in a clamp. Using AI assistance can shift the work from “microcraft every sentence” to “direct, review, and refine.” That often means less keyboard time, less strain, and less of that shallow breathing loop where your body forgets to breathe because your mind is trying to perfect a paragraph.

There is also a psychological benefit that is hard to quantify. When the “blank page” is no longer a wall, you show up more consistently. You are less likely to procrastinate. You do not need a perfect burst of inspiration to begin. You can begin by conversing, and then shape the conversation into prose.

That does not make the writing less human. It makes the writing more possible.

5. The costs, and the real ways this can go wrong

The downside is also real, and if we normalize CENTAUR writing, we should say the risks out loud.

The first risk is hallucination, meaning the chatbot states something as fact that is not true. This is not rare. It can be subtle. It can be a date that is off. It can be an invented citation. It can be a confident summary of a paper it never actually read. If you publish without verification, you will eventually publish errors.

The second risk is what I call polished mediocrity. The chatbot is very good at producing paragraphs that sound like an essay. It is good at “essay voice.” The danger is that you end up with text that feels substantial but is not. It is smooth, generic, and forgettable. It can become AI slop. Not because the tool is evil, but because the workflow did not force specificity and thinking.

The third risk is homogenization. If many people lean on the same kind of assistant, writing can converge. You start seeing the same rhetorical moves, the same transitions, the same safe conclusions. Even if the writing improves locally, culture can become flatter globally. If you care about voice and originality, you have to actively protect them.

The fourth risk is skill atrophy. If you never struggle with phrasing, you may lose some of your own ability to do it. More importantly, if you let the chatbot do your thinking, you will get weaker as a thinker. The tool should relieve the cost of expression, not replace the act of forming a view.

The fifth risk is privacy and confidentiality. People paste everything into chats. Drafts. Personal stories. Work documents. Sensitive material. If we normalize CENTAUR writing, we also need to normalize boundaries. Not everything belongs in a prompt.

The sixth risk is trust. Readers want to know who is speaking. They want to know whether the author actually means what is written. If AI assistance becomes common and undisclosed in contexts where disclosure matters, trust can erode. And once trust erodes, everyone pays the price, including careful writers.

So yes, CENTAUR writing is an advantage. But it is not a free lunch. It is a tool that increases power. When power increases, responsibility has to increase with it.

Still here? Wondering why I capitalized centaur throughout? Well I did it once because I was using voice to text which was not properly recognizing the term (sent our). ChatGPT latched onto that and irresponsibly capitalized each letter thereafter. Small, accidental choices in the human prompt can become “policy” for the whole piece. I left it in to show how easy it is for unintended mistakes and issues to creep in.

Jared Edward Reser PhD with ChatGPT 5.2

Leave a comment