This essay builds upon the concepts introduced in “AI-Mediated Reconstruction of Dinosaur Genomes from Bird DNA and Skeletons” (Reser, 2025). You can read the full original proposal here:

https://www.observedimpulse.com/2025/07/ai-mediated-reconstruction-of-dinosaur.html?m=1

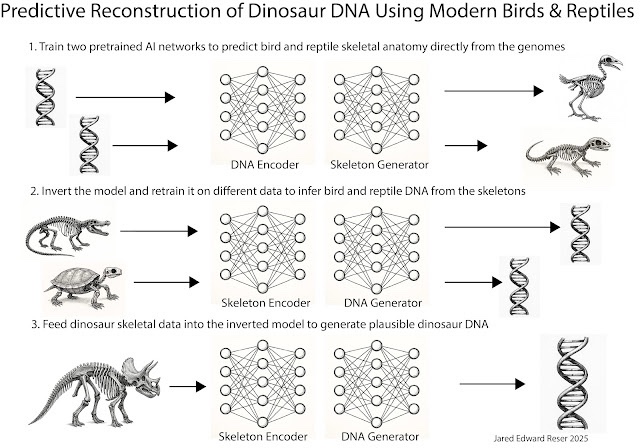

In that proposal I outlined a three tiered machine learning pipeline where an AI system is trained to learn the mapping from the genomes of different species of birds and reptiles to their respective skeletons. The neural network system is then inverted and trained on other species to predict genomes from skeletons. At that point, you could provide the system with a dinosaur fossil, and it would output plausible DNA based on what it knows about birds and reptiles. In this essay, I take that idea and relate it to information decompression.

1. Paleontology as data recovery, not just description

When we look at a dinosaur fossil, we usually treat it as an object. A relic. A thing that can be measured, categorized, compared, and displayed. That is valid, and it has produced an astonishing amount of knowledge. But it also subtly narrows what we imagine is possible. It makes paleontology feel like a science of inference from fragments, where the fragments define the ceiling.

My proposal starts with a different framing. A fossil is not just an object. It is a file. More specifically, it is a damaged, partial, and heavily compressed recording of a biological system. If you accept that, then a dinosaur skeleton is not merely evidence of existence. It is information. And the core scientific question becomes an information question: what signal is preserved, what signal was discarded, what signal was corrupted, and what kind of decoder could recover what is recoverable?

This is why digital signal processing and information theory feel like the right metaphors, and more than metaphors. They give us a vocabulary for the real structure of the problem. A living organism is a vast, high-dimensional dataset. Fossilization is not just “loss,” it is a specific kind of channel that preferentially preserves some information and destroys other information. What remains is not arbitrary. It is biased. It is patterned. It is constrained by the very biology that produced it.

That framing also immediately clarifies what I am not claiming. I am not claiming we can retrieve the exact genome of a particular individual animal from 66 million years ago, base pair by base pair, as if the bone were a USB drive holding the original file. That would misunderstand what compression is and what time does. I am claiming something more careful and, I think, more defensible. We can reconstruct a consensus genome, meaning a plausible genome that is constrained by phylogeny and development, and that would generate the observed dinosaur phenotype when run through the archosaur developmental machinery.

In my original essay, the practical motivation was straightforward. We already have enormous genomic resources for modern birds and reptiles. We have rich fossil data for dinosaurs, including extremely detailed skeletal morphology and, in some cases, soft tissue impressions, integument traces, eggs, growth rings, and other biological hints. We also have rapidly advancing sequence models and multimodal machine learning systems that can learn complex mappings from high-dimensional inputs. The idea is to connect those facts into a pipeline: use living archosaurs to learn the relationship between genomes and skeletal outcomes, then use dinosaur skeletons as constraints to infer the most probable genetic architectures consistent with those constraints.

If this sounds ambitious, that is because it is. But the ambition is not “magically recover the past.” The ambition is “treat fossils as compressed data and build a decoder.”

2. Low bit rate encoding in biology: the skeleton as lossy compression

A useful way to think about the genome is as a master file, like a RAW image. It is enormous and information-rich. It contains coding sequence, regulatory structure, developmental control logic, and huge regions of sequence that are neutral or context-dependent. It contains individual quirks that may never express and variations that change almost nothing about the body plan. It also contains many redundancies and many different routes to similar functional outcomes.

Development takes this master file and compiles it into a body. That compilation is compressive in a very literal sense. A phenotype is an expression of genomic information, but it is not a mirror of the genome. Much of the genome never shows up in gross anatomy. Some of it expresses in subtle ways. Some expresses only under particular environments, developmental contingencies, or disease states. So even before fossilization begins, the organism is already a compressed representation of its genome.

Then fossilization imposes a second compression, and it is far harsher. Soft tissue rots, pigments fade, organs vanish, behavior disappears almost entirely except through indirect traces like trackways or bite marks. Bone survives more often, and even bone is altered, mineralized, distorted, and fragmented. You can think of this as an encoder that outputs a low bit rate file plus heavy noise and missing data.

This leads to the central thesis: a skeleton is a lossy compression of the genome.

In a JPEG, the compressor keeps broad, low-frequency structure and discards high-frequency detail. The overall shape is preserved. The fine texture is sacrificed. The image still looks like the scene, but specific grains of sand are gone forever.

In biology, something similar happens. The skeleton preserves information that is tightly coupled to skeletal development and biomechanics, including limb proportions, joint architecture, lever arms, scaling relationships, and aspects of growth dynamics. It discards information that does not reliably imprint on bone, including most of the details of soft tissue, many immunological idiosyncrasies, and countless individual variants that do not significantly affect skeletal phenotype.

This is not just a rhetorical move. It is what makes the problem coherent. If the skeleton preserved nothing systematic about the genome, then there would be no research program here. But if the skeleton is a structured, low bit rate recording of the organism’s developmental program, then it is not insane to attempt inference.

The key is to treat “lossy” as a scientific constraint rather than a fatal objection. Lossy compression does not mean “nothing can be recovered.” It means “you cannot recover the exact original.” In information theory terms, you should not expect invertibility. You should expect an underdetermined inverse problem. Many genomes can map to similar skeletal outcomes, especially once you account for redundancy, buffering, and degeneracy in biological systems. That underdetermination is precisely why perfect cloning is impossible and why consensus reconstruction remains meaningful.

3. Super resolution for extinct life: methodology and the De-extinction Turing test

Once you accept that a fossil is a lossy, corrupted file, the right computational analogy is not “decompression” in the naive sense. The right analogy is super resolution.

When modern AI upscales old footage, it does not recover the true missing pixels. It generates plausible pixels that fit the low-resolution input and match the statistical structure it learned from high-resolution examples. It is a constrained hallucination, but constrained in a principled way. It produces an output that is faithful in structure even if it is not identical in microscopic details.

That is the role I am assigning to the AI system in this project.

Methodologically, the proposal is a multimodal inverse problem with a strong prior:

Training data: paired examples from living animals where we have both genome and phenotype. The obvious foundation is archosaurs, meaning birds and crocodilians, extended with other reptiles and, where useful, mammals as negative contrast classes. The critical point is that the model must learn within a phylogenetic style. It must learn archosaur ways of building bodies, not generic vertebrate averages. Phenotype encoding: the skeletal phenotype must be represented richly. Not just crude measurements, but high-resolution 3D geometry and, when possible, microstructural features. A human sees “robust femur.” A model can learn patterns in trabecular architecture, cortical thickness gradients, vascular channel distributions, and attachment surface geometry, which together carry information about growth rate, loading regimes, and developmental constraints. Model objective: learn a shared latent space, a bidirectional manifold, where genomes and skeletal phenotypes map into a joint representation. Forward direction is genotype to phenotype. Inverse direction is phenotype to a distribution over genomes or genome features that are consistent with that phenotype and consistent with the archosaur prior. Inference on fossils: treat the dinosaur skeleton as a multimodal prompt. The prompt constrains the search space. The model then generates a consensus genome, or more realistically, a family of genomes, that would plausibly generate an organism consistent with the fossil constraints.

This is where the “Da Vinci style” idea matters. Biology has style, and we usually call it phylogenetic constraint. Archosaurs share developmental toolkits and regulatory architectures that shape what is plausible. A missing stretch of genomic information should be completed using archosaur logic, the same way an art restoration model fills missing content using Da Vinci-like constraints rather than Picasso-like constraints. The output does not need to replicate the cracks in the original paint. It needs to reproduce the coherent structure.

That brings us to the right success criterion, and this is where I want to be explicit.

If we demand the historical genome, we will always fail because the compression destroyed information. So we need a functional standard. I propose what I call the De-extinction Turing test. It is a deliberately provocative name, but it captures the idea cleanly. If a reconstructed consensus genome, when instantiated in a viable developmental context, produces an organism whose phenotype and biomechanics are indistinguishable from what we mean by “that dinosaur” within measurement limits, then the reconstruction is successful. It does not matter if neutral variants differ or if individual-specific susceptibilities are not recovered. Those details were not reliably preserved by the compression pipeline, so demanding them would be demanding magic.

This reframes the goal from “time travel” to “porting.” We are not trying to resurrect a specific individual. We are trying to recover the functional architecture of a lost organism class under the constraints of archosaur development. In the same way, a restored, upscaled image can be faithful to the scene without recovering the exact original pixels, a reconstructed dinosaur genome can be faithful to the organism without matching the exact historical sequence.

In the next sections, I will extend this framework with two ideas that make it stronger rather than weaker. First, biology contains natural error correction and redundancy, which widens the target and makes functional recovery more plausible. Second, the fossil-as-prompt view clarifies why this is not unconstrained imagination but constrained completion, and why better measurements of fossils directly translate into better reconstructions.

4. The fossil as a prompt, and why measurement matters so much

Once you see the skeleton as a compressed file, you also start seeing it as a prompt. Not a poetic prompt, but a high-dimensional conditioning signal.

In a language model, the prompt constrains the space of completions. A short prompt produces a wide distribution. A long, specific prompt collapses the distribution toward a smaller set of plausible outputs. A fossil works the same way. A single femur is a prompt, but it is a weak one. A complete skeleton is a strong prompt. A skeleton paired with histology, growth marks, trackways, and preserved integument traces is a very strong prompt.

This is why the methodology is not just “apply AI.” The method is: increase the information content of the prompt, then use a model that has learned the relevant priors to complete what the prompt implies.

It also explains why people sometimes underestimate the amount of recoverable signal in bone. A macroscopic photograph is one channel. A high-resolution 3D mesh is another. Micro-CT and histology open additional channels. Geochemistry and isotopic signatures add still more. Each channel narrows the posterior.

A human paleontologist is superb at interpreting the features we have learned to notice, but we are bottlenecked by attention, by training, and by what our eyes and intuitions can parse. A model can treat the skeleton as a dense vector of measurements across multiple scales and learn correlations that are not obvious, even if they are real.

To be clear, no single microstructural feature “equals” a gene. But that is not how super resolution works either. It works by using a large set of weak constraints that jointly become strong. The model does not need a one-to-one mapping. It needs enough structure to locate the fossil within the right region of the learned manifold.

This point matters for critics, because it turns the project from hand-wavy speculation into a measurable research program. If we can show that increasing the fidelity of the fossil prompt improves reconstruction accuracy on extant holdout tests, then we have a clear empirical lever. Better scans, better reconstructions. That is a scientific relationship, not a narrative.

5. Biology’s error correction and redundancy, and why it helps the reconstruction

Information theory also tells us something that is easy to miss if you are thinking in terms of perfect decoding. In many engineered systems, redundancy and error correction are designed to make noisy channels usable. Biology is saturated with analogous properties.

There is redundancy at the genetic code level. Codon degeneracy means many different sequences map to the same amino acid. There is redundancy in regulation. Many gene regulatory networks tolerate variation without catastrophic phenotype changes because function is distributed across motifs and interactions rather than a single brittle string. There is redundancy at the systems level. Multiple different micro-level configurations can yield the same macro-level output.

This is sometimes described as robustness, buffering, or degeneracy. I like degeneracy as a term because it captures the idea that different components can perform overlapping functions. The practical implication is simple.

The target we are trying to hit is not a pinhole. It is a basin.

If “a functional T. rex” corresponds to a broad region in genotype space that maps to a relatively narrow region in phenotype space, then the inverse problem becomes more tractable. The model does not need to recover the unique historical genome. It needs to land within the basin of genomes that produce the right organism under archosaur development.

This is also where the lossy compression thesis becomes an advantage instead of a concession. In lossy systems, you should not expect a reversible mapping. You should expect classes of originals that compress to similar outputs. That is exactly what biology gives us. And it means a consensus reconstruction can be scientifically meaningful even when the historical details are unrecoverable.

This is the place in the essay where I would emphasize something that can sound counterintuitive at first: underdetermination is not always the enemy. It is often a sign that the system has slack. That slack is what makes functional recovery possible.

6. The De-extinction Turing test, and what counts as success

If we accept the limits imposed by lossy compression, then we must also be honest about how we evaluate success. We cannot validate an inferred dinosaur genome by comparing it to the original, because we do not have the original.

So we need an operational criterion.

I introduced the De-extinction Turing test as a way to name this. The idea is to define success by output behavior, not by hidden internal identity. If a reconstructed consensus genome, instantiated in a viable developmental context, yields an organism whose anatomy, growth dynamics, and biomechanics are indistinguishable from the inferred dinosaur within the resolution of our measurements, then the reconstruction is successful.

This is a strong claim, but it is also an appropriately bounded one. It does not say “we recreated the exact individual that lived.” It says “we recreated an organism that belongs to the target class and expresses the functional architecture implied by the fossil evidence.”

There is a deeper reason to like this standard. It matches how we already treat many scientific reconstructions. We routinely accept models that reproduce the macroscopic behavior of a system without claiming microscopic identity. We accept climate models because they reproduce key dynamics, not because they reproduce each molecule of air. We accept reconstructed neural models when they reproduce the relevant computations, not when they reproduce each synapse.

Here, the phenotype is the behavior of the genome under the developmental compiler. The fossil is a partial recording of that phenotype. The best we can demand is that our inferred genome, when run forward, recreates what the fossil records and what phylogeny permits.

This is also the cleanest response to the “impossible” crowd. It concedes exactly what must be conceded. Some information is gone forever. At the same time, it defines a victory that is both meaningful and testable in principle.

7. What this changes, and the right way to talk about it

If this approach works even partially, it changes what paleontology can be. It turns fossils from static objects into compressed biological archives that can be decoded. It shifts paleontology toward a science of latent biological architectures, where the goal is not only to describe forms but to infer the developmental and genetic programs that generated them.

It would also change how we talk about extinction. Extinction would still be extinction. We would not be resurrecting the past in a literal sense, and we should never pretend otherwise. What we would be doing is recovering lost designs, lost solutions that evolution once found, and reconstructing them within modern constraints. That is a different claim. It is less cinematic, and it is more honest.

There is also an ethical layer here, and I want to acknowledge it without turning the essay into a moral lecture. The ability to reconstruct functional architectures of extinct organisms would create obvious temptations. Some would be scientific, some would be commercial, some would be reckless. That is not a reason to avoid the idea, but it is a reason to keep the argument precise and to keep the success criteria grounded.

The point of this essay is not to claim that we will have a living T. rex next decade. The point is to show that the logic of the problem is coherent when framed correctly. Compression and super resolution are not cute metaphors. They describe the structure of the pipeline that already exists in nature, and the kind of computational tool that could act as its partial inverse.

A dinosaur skeleton is a low bit rate recording of a genome, degraded by time. An AI system trained on extant genotype–phenotype pairs could act as a phylogenetically constrained upscaler, generating a consensus genome that preserves the functional architecture implied by the fossil evidence. We should not demand pixel-perfect recovery, because biology itself did not preserve pixel-perfect information. We should demand functional recovery under a clear operational test, which is what the De-extinction Turing test is meant to capture.

In that sense, paleontology starts to look less like the study of rocks and more like data recovery from corrupted hard drives. We have the files that survived. We have the priors. The question is whether we can build the decoder.

Leave a comment