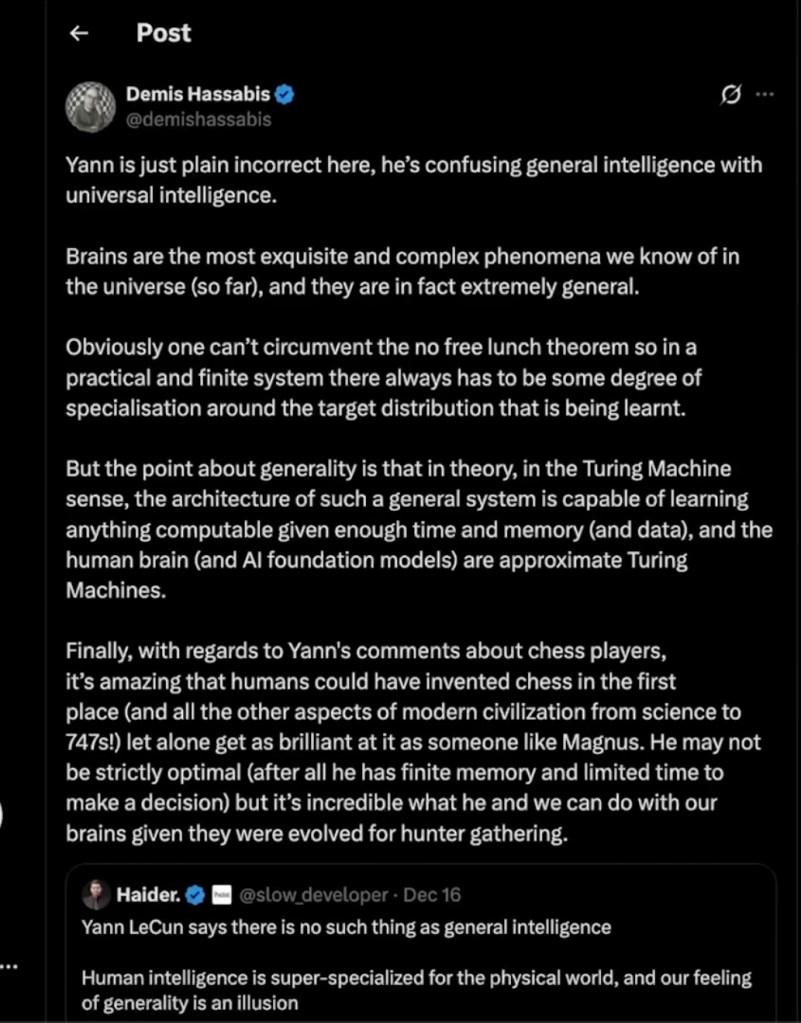

Two AI researchers can look like they are arguing about whether general intelligence exists, when they are really arguing about definitions and emphasis. That is what I hear in the Hassabis vs. LeCun exchange. Underneath the sharp tone, the disagreement collapses into a useful tension: scaling versus structure, breadth versus efficiency, and “general” versus “universal.”

The key distinction: “general” is not “universal”

A lot of heat in this debate comes from treating two different ideas as if they were the same.

General intelligence, in the practical AGI sense, means broad competence. It means the ability to learn many skills, transfer knowledge across domains, adapt to novelty, and keep functioning when conditions shift. This is the “can it do lots of things in the real world” definition.

Universal intelligence (as an ideal) is an intelligence that can succeed across an extremely wide range of possible environments and tasks because it is not locked into a narrow set of built-in assumptions about how the world must be. It has as few “hard-coded” commitments as possible, and the commitments it does have are the ones that are truly necessary for learning at all.

Universal intelligence is a theoretical extreme. It is the idea of an agent that could, in principle, perform well across essentially any environment or problem space, often framed as any computable task under some assumptions. It is an idealized ceiling, not a realistic engineering target. You can still talk about being “more or less universal” in practice, but universal itself is the asymptote.

This is why the distinction matters. If someone quietly upgrades “general intelligence” into “universal intelligence,” then it becomes easy to dismiss general intelligence as impossible. But that is a rhetorical move, not a scientific conclusion. Humans are general in a meaningful sense without being universal in the fantasy sense.

Priors and inductive bias: the hidden engine of generalization

The debate also turns on two words that people use loosely: priors and inductive bias.

Bias here does not mean prejudice. It means a built in leaning. Induction is the act of going from examples to a general rule. Inductive bias is the set of assumptions that guide how a learner generalizes when many explanations could fit the same data.

A prior is the same idea in Bayesian language. A prior probability is what you assume before the new evidence arrives. In modern machine learning, priors often show up implicitly through architecture, training objective, data selection, and optimizer dynamics. People call these “inductive biases” because they tilt the learner toward certain kinds of solutions.

This matters because generalization is impossible without assumptions. Data never uniquely determines the rule. Something has to tilt the learner toward certain explanations and away from others.

LeCun’s side: human generality is partly an illusion

LeCun’s core point, as I interpret it, is that human intelligence looks general because it is built on powerful assumptions tuned to the physical and social world. Our brains come with deep biases about objects, time, causality, agency, and compositional structure. Those assumptions make learning efficient.

So when people say “humans can do anything,” LeCun hears an overstatement. Humans are not universally competent across all imaginable worlds. We are competent inside the kind of world we evolved to model.

This connects directly to the concept of umwelt. Every organism inhabits a species specific perceived world shaped by its sensory channels, motor capacities, and evolutionary history. A tick does not live in the same world a human lives in. A bat does not live in the same world a dog lives in. Umwelt is a reminder that intelligence is never floating free from embodiment and perception. It is constrained and sculpted by what the agent can detect, what it can do, and what regularities its learning system is tuned to pick up.

Applied to AI, the point becomes sharp: the architecture and training regime determine what the system can “see,” what it compresses, and what it will systematically miss. Scaling can enlarge capability, but it does not automatically fix blind spots caused by the way the system interfaces with the world.

Hassabis’s side: brains are genuinely general, and general is not universal

Hassabis’s core point is that humans display an extraordinary kind of generality. We evolved in a narrow ecological niche, yet we can learn chess, mathematics, medicine, and aerospace engineering. That breadth is not a trivial illusion. It is evidence of a highly flexible learning system that can be redirected far beyond its original purpose.

When Hassabis leans on the “in principle” argument, he is pointing at a different axis: representational capacity and learnability. A sufficiently powerful learning system can implement a vast range of internal models and behaviors. In that sense, brains are general purpose learning machines.

The AI implication is straightforward. Scaling is not naive. Scaling can widen competence, and that competence can be widened further with memory, planning, multimodal grounding, and tool use. The system does not need to be universal in the extreme theoretical sense for general intelligence to be real in the practical sense.

But there is a possible blind spot here. If umwelt is fundamental, then “generality” is always conditional on the perceptual and action interface. A system can look general inside the world it is built to perceive, while remaining narrow or brittle outside that envelope. In that sense, it is possible to underweight how strongly intelligence is shaped by what the agent is built to notice.

My synthesis: both are right, and the path forward is a feedback loop

Both researchers are right about something important.

LeCun is right that generalization requires inductive bias and that humans are not universal across all possible worlds. The “no free lunch” intuition is real. Without assumptions, you cannot generalize efficiently.

Hassabis is right that humans are meaningfully general in the sense that matters for AGI, and that scaling can produce real increases in breadth. Also, “general” does not mean “universal,” so it is unfair to knock general intelligence by attacking an impossibly strong definition.

The productive synthesis is that scaling and bias are not enemies. Scaling is one of the ways to learn what your biases should be.

The hindsight loop: why scaling can teach better priors

It is easy to say “just pick the right priors,” but in practice the hard part is knowing what those priors should be and how to implement them. Some biases can be guessed in advance, such as temporal continuity, objectness, causality, compositional structure, and social agency. But the exact recipe and the implementation details are often discovered only after systems are pushed far enough to expose their characteristic failures.

That is where hindsight comes in. Large scale systems function like experimental instruments. As you scale, you get broader competence and also a broader map of failure modes. Those failure modes tell you where your assumptions were wrong or incomplete.

Then you update. In Bayesian language, you revise your priors. In engineering language, you change inductive bias through architecture, objectives, training regimes, memory, planning, grounding, and the structure of the environments the model learns in. Then you scale again.

This creates an iterative climb:

Start with imperfect priors Scale to expand generality Observe failures under novelty Adjust priors and inductive bias Scale again

In umwelt terms, this is also a loop of expanding and refining the agent’s effective world. Better sensors, better action interfaces, better training environments, and better internal representations all change what the system can even notice, which changes what it can learn.

Tone and fairness: why the “incorrect” call felt unnecessary

There is also an interpersonal layer. Hassabis came off more aggressive, calling LeCun incorrect. That feels unnecessary because LeCun’s warning is not a refutation. It is a constraint. Meanwhile, LeCun can go too far if the warning hardens into pessimism, implying that these issues block AGI in principle. Humans clearly exhibit a real form of generality, and AI systems can plausibly exceed it.

So the balanced position is simple:

Hassabis is right that scaling is a real path to AGI and that “general” is meaningful LeCun is right that inductive bias matters and that scaling without structure is partly blind Hassabis was too dismissive in tone LeCun would be too pessimistic if he concludes these issues make AGI impossible

Where this leaves AI

The debate is not scale versus structure. It is scale plus structure, with a feedback loop between them. Scaling increases reach. Reach reveals missing structure. Structure increases efficiency and robustness. Efficiency enables further scaling.

That is how a system becomes not merely bigger, but more genuinely general, and gradually less parochial in its assumptions. In other words, closer to universality on a continuum, even if perfect universality remains a theoretical ideal.

Leave a comment