I. Introduction: Why Intelligence Requires Iteration

Human intelligence does not operate in a single pass. Thought unfolds as a sequence of partially overlapping internal states, each one shaped by what came immediately before it. This temporal structure is not an implementation detail; it is the foundation of cognition itself. At every moment, a limited set of items occupies working memory, attention biases which of those items persist, and long-term memory is queried to supply what comes next. The mind advances not by jumping directly to conclusions, but by iteratively refining its internal state.

Most contemporary artificial intelligence systems, by contrast, excel at powerful single-pass inference. Even when they generate long outputs, those outputs are produced within a single, frozen internal trajectory. The system does not revisit its own prior internal states, does not reconsolidate memories over time, and does not gradually restructure its long-term knowledge through use. As a result, these systems can be fluent and capable while remaining fundamentally static.

The central claim of this essay is that iteration is the engine of intelligence, and that its long-term consequence is compression. Specifically:

• Iterative updating in working memory is the basic mechanism of thought.

• Iterative compression in long-term memory is the cumulative result of that mechanism operating over time.

This framing unifies attention, learning, abstraction, and inductive bias formation within a single cognitive algorithm. Iteration is not merely how we think in the moment; it is how thinking reshapes memory so that future thought becomes simpler, faster, and more general.

You can find my writings about this at aithought.com and here are the published articles I’ve written on the subject:

A Cognitive Architecture for Machine Consciousness and Artificial Superintelligence: Updating Working Memory Iteratively, 2022 arXiv:2203.17255

And

⸻

II. The AIThought Model: Iterative Updating in Working Memory

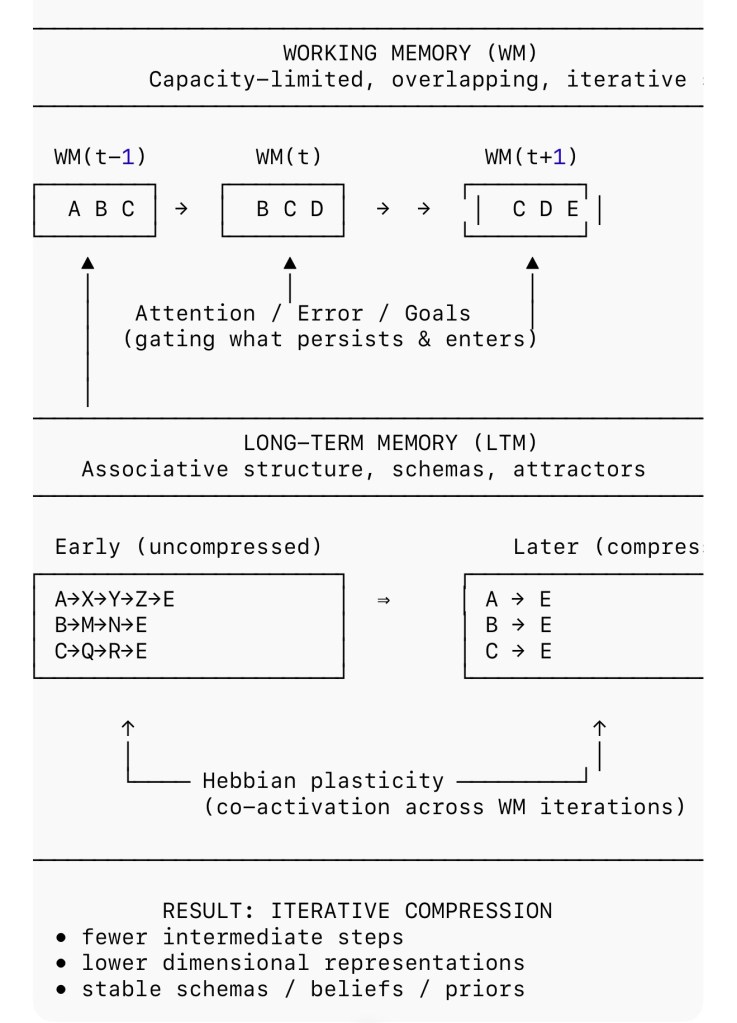

In the AIThought framework, working memory is conceived as a capacity-limited, self-updating buffer that evolves through discrete but overlapping states. At any given moment, only a small subset of representations can be simultaneously active. Thinking proceeds by transitioning from one working-memory state to the next, rather than by operating on a static global workspace.

Each update follows a consistent pattern:

1. Retention: some items from the prior working-memory state persist.

2. Suppression: other items are actively inhibited or allowed to decay.

3. Recruitment: new items are added, drawn from long-term memory via associative search.

Crucially, successive working-memory states overlap. This overlap creates continuity, prevents combinatorial explosion, and allows thought to proceed as a trajectory through representational space rather than as a sequence of disconnected snapshots.

In this model, thinking is not the manipulation of symbols in isolation. It is a path-dependent process, where each intermediate state constrains what can come next. The system does not evaluate all possibilities at once; it incrementally narrows the space of possibilities through repeated updates.

This iterative structure explains why complex reasoning often requires time, why insight arrives gradually, and why premature conclusions are brittle. Intelligence emerges not from a single optimal inference, but from a controlled sequence of partial revisions.

⸻

III. Attention as a Control Signal Over Iteration

Attention plays a decisive role in determining how iteration unfolds. Rather than acting as a passive spotlight, attention functions as a control signal that shapes both the contents of working memory and the direction of long-term memory search.

At each update, attention biases:

• which items remain active,

• which associations are explored,

• which representations are suppressed,

• and which memories become eligible for plastic change.

Error signals, affective salience, goal relevance, and novelty all modulate attention. These signals do not dictate conclusions directly; instead, they influence which iterations occur and which do not. Attention determines where the system spends its limited iterative budget.

Importantly, attention operates over time. A fleeting stimulus may briefly enter working memory, but only sustained or repeatedly reactivated items participate in deeper iterative processing. This temporal gating ensures that learning is selective and that memory is not overwritten indiscriminately.

In the AIThought model, attention is therefore inseparable from iteration. It is the mechanism by which the system allocates its finite cognitive resources across competing representational trajectories.

⸻

IV. From Iterative Updating to Learning: How Working Memory Changes Long-Term Memory

Iterative updating in working memory does not merely support moment-to-moment cognition; it is also the primary driver of learning. Each iteration creates patterns of co-activation among representations, and over repeated iterations these patterns leave lasting traces in long-term memory.

When the same sets of items are repeatedly co-active across working-memory states, Hebbian plasticity strengthens the associative links among them. Conversely, items that are consistently suppressed or excluded from successful trajectories are weakened. Over time, this process reshapes the associative structure of long-term memory.

The key consequence is compilation. Early in learning, reaching a solution may require many intermediate working-memory states. Later, after repeated iterations, the same initial cues can directly recruit the solution with far fewer steps. What was once an extended search trajectory becomes a short associative path.

Long-term memory does not store conclusions as static facts. Instead, it stores shortcuts—compressed pathways that reproduce the outcome of prior iterative processes without re-enacting them in full. Learning, in this sense, is the gradual replacement of slow, explicit iteration with fast, implicit recruitment.

This explains why expertise feels intuitive, why practiced reasoning becomes automatic, and why insights that once required effort later appear obvious.

⸻

V. Iterative Compression: The Long-Term Consequence of Iteration

The cumulative effect of iterative updating and learning is iterative compression.

Iterative compression can be defined as the progressive reduction of representational complexity across repeated reformulations, constrained by the requirement that functional performance be preserved. With each pass, redundant details are stripped away while invariant structure is retained.

Compression is not loss of meaning; it is the removal of unnecessary degrees of freedom. Representations that fail to generalize across contexts are pruned. Representations that survive repeated rewriting become stable, abstract, and reusable.

From this perspective, beliefs, schemas, and concepts are attractor states in representational space—configurations that remain stable across many iterations and many contexts. They are not arbitrarily chosen; they are what remains after everything that could not survive repeated compression has been eliminated.

A defining feature of iterative compression is that it is visible primarily in hindsight. Only after multiple reformulations does it become clear which aspects of a representation were essential and which were incidental. This explains the familiar sense that good explanations feel inevitable once discovered, even though they were anything but obvious beforehand.

Iterative compression is therefore the trace that iteration leaves in long-term memory. It is how intelligence becomes more efficient over time, how abstraction emerges from experience, and how inductive biases are gradually earned rather than pre-specified.

⸻

VI. Dimensionality Reduction and Generalization

Iterative compression naturally produces dimensionality reduction. Each cycle of reformulation removes representational degrees of freedom that do not consistently contribute to successful prediction, explanation, or control. What remains is a lower-dimensional structure that captures what is invariant across contexts.

This process explains how generalization emerges without being explicitly programmed. Early representations are often rich, episodic, and context-bound. As they are repeatedly reconstructed and compressed, context-specific details are discarded while relational structure is preserved. The system gradually shifts from encoding what happened to encoding what matters.

Generalization, on this account, is not extrapolation from a static dataset. It is the byproduct of repeated failure to compress representations that are too brittle or too specific. Only representations that remain useful across many reformulations survive.

This also explains why overfitting is unstable in biological cognition. Representations that depend on narrow contingencies tend to collapse under iterative compression, whereas representations that capture deeper regularities remain viable.

⸻

VII. Iterative Compression and the Formation of Inductive Bias

Inductive biases are often treated as prior assumptions built into a system from the start. In practice, many of the most powerful biases are learned rather than specified. Iterative compression provides a mechanism for how this occurs.

As representations are repeatedly compressed, the system discovers which distinctions matter and which do not. Over time, this reshapes expectations about the world. Certain patterns become default assumptions not because they were hard-coded, but because alternative representations repeatedly failed to survive compression.

In this way, inductive bias is the residue of past iteration. It reflects what has proven compressible under real constraints, not what was assumed to be true a priori. Biases are therefore earned through experience and hindsight, not imposed in advance.

This perspective reconciles two competing intuitions about intelligence:

• that powerful priors are necessary for learning

• and that those priors cannot be known in advance

Iterative compression resolves the tension by allowing priors to emerge gradually, shaped by repeated engagement with the world.

⸻

VIII. Comparison to Artificial Systems

Modern artificial intelligence systems, particularly large language models, perform substantial compression during training. However, this compression is largely offline and frozen. Once training is complete, the internal representations no longer change in response to use.

During deployment, such systems may generate long outputs, but they do so within a single internal trajectory. They do not revisit prior internal states, reconsolidate memories, or iteratively rewrite their long-term knowledge. As a result, insights do not compound across interactions.

From the perspective of iterative compression, this is a fundamental limitation. Compression occurs once, rather than repeatedly. The system does not discover new inductive biases through use, nor does it simplify its representations over time.

Achieving more human-like general intelligence would require architectures that support:

• persistent working memory with overlapping states

• replay of prior internal trajectories

• plastic long-term memory that can be rewritten

• and constraints that preserve performance while allowing simplification

Without these features, artificial systems can be powerful but remain static—capable of impressive inference, yet unable to truly learn from their own thinking.

⸻

IX. Thought, Writing, and Science as Iterative Compression

The same algorithm that governs individual cognition also governs scientific and intellectual progress. Scientific theories are not discovered fully formed; they emerge through cycles of formulation, critique, revision, and simplification.

Drafts function as memory traces. Revisions act as reconsolidations. Each pass removes unnecessary assumptions, clarifies invariants, and exposes boundary conditions. Weak theories collapse under rewriting; strong theories become simpler and more general.

The subjective sense that a mature theory feels “obvious” is the experiential signature of successful compression. Once a representation reaches a stable, low-complexity form that preserves explanatory power, it no longer feels contingent.

From this view, science is not the accumulation of facts, but the progressive compression of experience into generative models that can survive repeated reformulation.

⸻

X. Implications for Machine Intelligence and Consciousness

If iterative updating is the engine of intelligence and iterative compression its trace, then systems lacking these dynamics will necessarily fall short of genuine general intelligence.

Moreover, the felt continuity of conscious experience may reflect the same underlying process. Consciousness is not a static state, but the lived experience of overlapping working-memory states evolving over time. The sense of a continuous present arises from iterative updating constrained by attention and memory.

While this account does not reduce consciousness to compression, it suggests that conscious awareness and learning share a common temporal architecture. Both require persistence, overlap, and revision across time.

A system that exists only in isolated inference episodes, without memory reconsolidation or iterative self-modification, may simulate aspects of intelligence without instantiating its core dynamics.

⸻

XI. Conclusion: Iteration Is the Engine, Compression Is the Trace

Intelligence is not defined by a single inference, a single representation, or a single pass through data. It is defined by the capacity to revise itself over time.

Working memory provides the stage on which iteration unfolds. Attention governs which trajectories are explored. Long-term memory records the residue of these processes, gradually reshaped through plasticity. Iterative compression is the cumulative result: the simplification of internal models without loss of functional power.

This framework unifies thinking, learning, abstraction, inductive bias formation, and scientific insight within a single process. It explains why hindsight is essential, why good explanations feel inevitable only after the fact, and why intelligence improves by becoming simpler.

In the end, intelligence is what remains after repeated rewriting removes everything unnecessary.

Leave a comment