I. Introduction: The Problem of Constant Evaluation

Modern humans spend an extraordinary amount of time evaluating themselves. We evaluate our performance, our social standing, our words before we say them, and even imagined versions of conversations that never occurred. Much of this evaluation happens automatically, beneath conscious awareness, and far faster than deliberate thought. While this capacity once served an essential evolutionary function, it now frequently becomes a source of fear, chronic stress, anxiety, and psychological suffering.

This essay argues that a significant portion of modern distress arises not from external danger or real failure, but from the brain’s error-detection systems firing inappropriately in safe environments. These systems evolved to protect us from threats and costly mistakes, but when they remain chronically active, they generate false alarms.

Over time, these false alarms take a psychological and physiological toll. I believe that these unconscious, negative reactions got to a point where they were running constantly and intensely in my brain in a tight loop that became inescapable for me. This error signaling has been amplified out of control and is now restructuring my experience of reality for the worse. But I believe that understanding what they are and how they affect us could help us escape them.

I propose that mental health and emotional regulation require not better evaluation, but the ability to turn evaluation off. I call this practice Voluntary Suspension of Evaluative Control, or VSEC. It is the intentional, temporary disengagement of performance monitoring, outcome judgment, and self-evaluation, allowing the nervous system to relearn what safety without vigilance feels like.

II. Evolutionary Origins of Fast Negative Reactions

Human brains evolved under conditions where mistakes were often costly. Failing to detect a predator, misreading a social signal, or making a poor foraging decision could result in injury, exclusion, or death. As a result, natural selection favored neural systems that prioritized speed over nuance. It was better to overreact than to underreact.

These systems generate fast, negatively valenced responses to perceived errors or threats. They operate largely outside conscious awareness and are biased toward false positives. In ancestral environments, this bias was adaptive. In modern environments, where physical danger is rare and social mistakes are rarely fatal, the same bias becomes maladaptive.

Importantly, individuals differ in how reactive these systems are. Some people have stronger, faster, and more persistent negative responses. These differences were likely beneficial in certain ecological niches, but today they often manifest as anxiety, rumination, rejection sensitivity, or chronic self-criticism.

III. The Brain’s Error-Detection Machinery

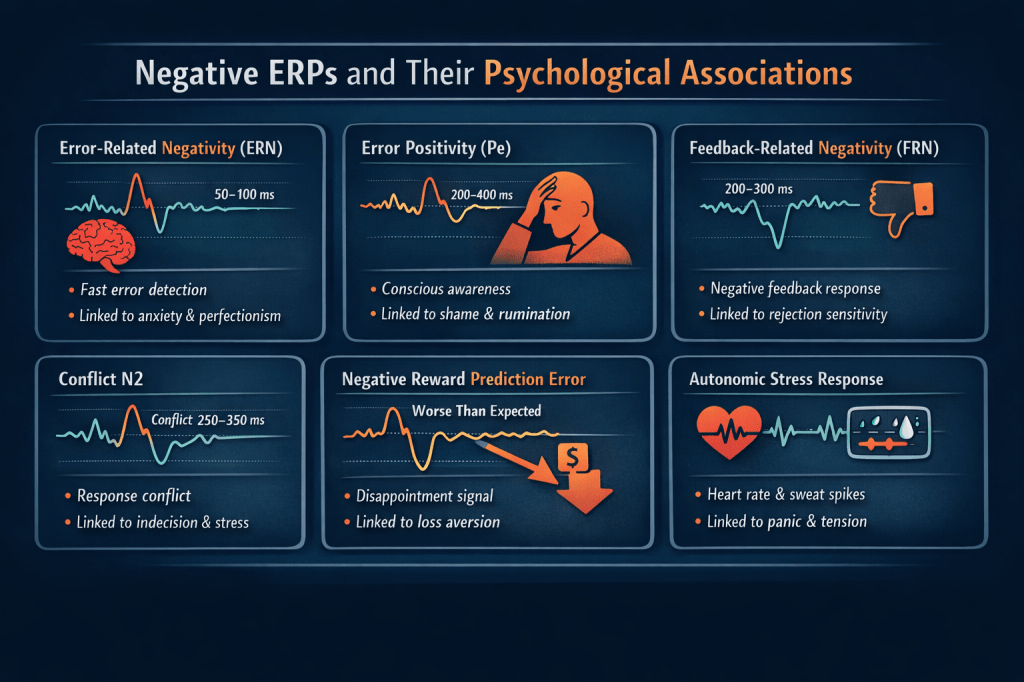

At the neural level, error detection is well studied. One of the most robust findings in cognitive neuroscience is the Error-Related Negativity (ERN). The ERN is a rapid electrical signal measured with an EEG skull cap that occurs approximately 50 to 100 milliseconds after a mistake is made. It is generated primarily in the anterior cingulate cortex, a region involved in performance monitoring, conflict detection, and outcome evaluation.

The ERN is unconscious. It occurs before a person realizes they made an error. Larger ERN amplitudes are associated with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive traits, perfectionism, and heightened sensitivity to mistakes. People with exaggerated ERNs often describe themselves as “hard on themselves” or unable to let errors go.

Following the ERN is the Error Positivity (Pe), a later signal associated with conscious awareness of an error and emotional appraisal. Larger Pe responses are linked to rumination, shame, and embarrassment.

Beyond EEG signals, negative evaluation engages the amygdala, which tags outcomes as threatening or aversive, and the brain’s reinforcement learning systems, which generate negative reward prediction errors when outcomes are worse than expected. These signals produce physiological arousal, stress hormone release, and shifts in posture, facial expression, and breathing.

Together, these systems form a fast, automatic loop that answers a single question: Something went wrong. How bad is it?

IV. Psychological Phenomena Linked to Negative ERPs

When error signals are frequent or exaggerated, they manifest psychologically in recognizable ways.

Anxiety disorders are associated with heightened ERN amplitude and hyperactive performance monitoring. Individuals experience constant internal alerts even in low-stakes situations.

Rejection sensitivity reflects exaggerated neural responses to social evaluation. Even imagined criticism or ambiguous feedback can trigger strong emotional reactions.

Catastrophizing occurs when small mistakes are interpreted as large failures. This reflects overgeneralization of error signals beyond their original context.

Rumination is the repeated reactivation of error-related circuits through internal rehearsal. The brain continues to signal “something is wrong” long after any actionable information has passed.

Perfectionism involves persistent self-evaluation and intolerance of error, often driven by fear-based reinforcement rather than intrinsic motivation.

Importantly, these reactions do not require real mistakes. Imagined conversations, anticipated conflicts, or hypothetical failures can activate the same neural machinery. The brain responds to simulated errors as if they were real.

V. Why Cognitive Control Often Fails

Most conventional approaches to emotional regulation focus on changing thoughts. People are encouraged to challenge negative beliefs, reframe situations, or think positively. While useful in some contexts, these strategies often fail to address the core problem.

The reason is simple: evaluation itself keeps the error-detection system active. Arguing with negative thoughts is still a form of monitoring. Positive thinking still involves judgment. Even self-compassion can become another task to perform correctly.

When individuals attempt to control or suppress negative reactions, they often increase vigilance. The brain remains in evaluative mode, scanning for mistakes in the regulation process itself. This creates a paradox where efforts to reduce anxiety amplify it.

VI. Voluntary Suspension of Evaluative Control

Voluntary Suspension of Evaluative Control offers a different approach. Instead of correcting evaluations, it removes the evaluative frame entirely.

VSEC is the intentional practice of temporarily disengaging performance monitoring, outcome judgment, and self-evaluation. Awareness remains intact. Sensation remains intact. What is suspended is the internal scoring system.

Evaluation requires a reference point. There must be a goal, an expectation, and a comparison. When those conditions are removed, error signals cannot fire. There is no success or failure, and therefore no error.

This is not suppression. It is not avoidance. It is a deliberate shift out of evaluative mode.

VII. The Non-Evaluative State

When evaluation is suspended, people often describe the resulting state as simple, naive, or childlike. There is a sense of mental quiet and reduced urgency. Some describe it as trance-like, though the term should be used cautiously. It is not dissociation or loss of awareness, but absorption without judgment.

In this state, predictive demands are lowered. The brain is not modeling outcomes or rehearsing future scenarios. Attention becomes present-centered and permissive rather than corrective.

This state often feels unfamiliar or even unsafe at first. Many people equate vigilance with responsibility and moral worth. Letting go of monitoring can feel like negligence. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. However, in safe environments, constant vigilance is unnecessary and harmful.

Dissociation as my most reliable “off switch”

There is a word for the mental move I reach for when I need to calm down fast, especially under pressure. Dissociation.

In clinical language, dissociation is a disruption in the normal integration of experience. Thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, memory, and even the felt sense of self do not bind together in the usual way. In mild forms, everyone recognizes it. You zone out. You go “blank.” You get absorbed and forget yourself for a while. In trauma-linked forms, it can show up as depersonalization, where you feel detached from your body or identity, or derealization, where the world feels oddly unreal. And there is also peritraumatic dissociation, the “shock-buffer” state some people enter during or immediately after overwhelming events.

I want to be careful here, because dissociation gets discussed like it is always pathology. It is not. It is also a protective reflex. When experience is too intense to metabolize, the nervous system can pull a very old lever. It dampens emotional pain. It creates psychological distance. It prevents overload. It can compartmentalize experience so you are not forced to integrate everything at once. In a genuinely threatening or inescapable situation, it may be the least bad option available. It buys time.

For me, dissociation is the most reliable way to relax in the face of adversity. I can do it intentionally. I simply step back.

I’m not me. I am no one.

I have no ego.

I have no concerns.

I have no guilt or anger.

This is mindless, vacant contentment.

I am totally zoned out regardless of my surroundings.

I’m just floating.

That might sound dramatic, but what I mean is simple. I can drop the identity layer that wants to perform, defend, win, explain, impress, or prove. I can feel the edges of that internal character loosen. And when that character loosens, a lot of “evaluative control” loosens with it. The inner scoreboard goes quiet. The constant micro-scanning of whether I am doing things right or whether someone approves of me fades into the background.

This is not denial. I do not use dissociation to pretend reality is not happening. I use it to keep myself from overreacting to reality.

It is the difference between perceiving and judging. Reality stays intact. The facts remain. The problem remains. The other person remains. What changes is that my system stops treating every stimulus like a referendum on my worth. I stop caring so much about what people think because the part of me that is always trying to manage their perception is no longer gripping the steering wheel.

In that sense, dissociation overlaps with what I am calling voluntary suspension of evaluative control. It is a mode shift. A temporary disengagement of the comparator that keeps asking: How am I doing? Did I fail? What does this mean about me? What do I need to fix right now? When that comparator quiets down, the error alarms do not cascade into spirals of rumination and social fear. The body can settle. The mind can breathe.

There is also a practical reason this works. Dissociation can blunt the emotional amplification loop that turns a small stressor into a full-body emergency. When the distress signal is lower, I can respond to the world with proportional force. I can still act. I can still problem-solve. I can still choose a boundary. But I am less likely to become reactive, defensive, or hooked.

One important caveat. Dissociation is a brilliant short-term strategy, but it is not always a great long-term home. If it becomes chronic, if it flattens life, if it creates memory gaps, if it makes relationships feel unreal, then it stops being a tool and starts becoming a cost. I’m describing something I use deliberately, in doses, as an off switch. I step out to regulate. Then I step back in to live.

So yes, I dissociate. I do it on purpose. And for me it is not an escape from reality. It is an escape from overreaction. It is how I keep the nervous system from treating every bump in the road like a catastrophe, and every social moment like a trial. It is how I turn down the internal evaluation, so that reality can be met as reality, not as a threat to the self.

VIII. Daily Practice and Neural Retraining

Error-reactivity is not fixed. ERN amplitude, autonomic tone, and recovery time are shaped by experience. Repeated entry into non-evaluative states retrains baseline neural gain.

Daily practice matters. Short, consistent periods of VSEC allow the nervous system to recalibrate. Over time, individuals experience reduced baseline tension, faster recovery after mistakes, and fewer false alarms.

This process resembles physical therapy more than insight-based change. It is not about understanding error systems intellectually, but about giving them regular periods of rest.

Imagined Bliss as Somatic-Affective Rehearsal

A useful analogy for understanding this practice is the familiar exercise of imagining eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. When a person vividly imagines the taste, texture, smell, and act of eating such a sandwich, the brain often responds as if a partial version of the experience is occurring. Salivation may increase. Appetite may be stimulated. The body begins to prepare for eating despite the absence of food.

This phenomenon illustrates an important principle: the brain’s affective and physiological systems respond to internally generated simulations, not only to external events.

The same mechanism can be applied to emotional states.

Instead of imagining the sensory details of eating a sandwich, one can imagine the felt experience of being deeply relaxed, low-pressure, safe, and content. The key is not to imagine a reason for happiness or a narrative justification, but to imagine the state itself. This includes the bodily sensations associated with ease, such as relaxed facial muscles, unforced breathing, softened posture, and the absence of urgency.

When practiced correctly, this does not involve telling oneself “I should be happy” or “things are going well.” Those thoughts reintroduce evaluation. Instead, the person attends to the somatic and affective texture of calm happiness as if it were already present.

From a neural perspective, this can be understood as somatic-affective rehearsal. The brain’s reward and autonomic systems are activated through internally generated signals, leading to real changes in physiology. Dopaminergic tone increases modestly. Sympathetic arousal decreases. Parasympathetic activity rises. The body begins to adopt the posture and rhythm associated with safety and satisfaction.

Importantly, this process bypasses performance monitoring. There is no task to complete and no outcome to judge. The imagined state is not something to be achieved, but something to be inhabited. As with imagining food, the nervous system does not require external validation to respond.

Over time, repeated rehearsal strengthens the association between conscious attention and relaxed affective states. The nervous system becomes more familiar with what low-pressure safety feels like, making it easier to access spontaneously. This reduces reliance on constant evaluation and weakens the grip of chronic error signaling.

The analogy is instructive because it reveals how little effort is required. Just as imagining a sandwich does not require cooking or eating, imagining calm happiness does not require solving life problems or eliminating stressors. It simply requires permission for the nervous system to simulate a state it already knows how to produce.

In this way, imagined bliss functions not as escapism, but as training. It reintroduces the nervous system to a mode of operation that evolved long before constant vigilance, optimization, and self-monitoring became the norm.

IX. Positive Affect Without Evaluation

Many people find it helpful to pair VSEC with imagined positive states, such as recalling feelings of happiness, safety, or contentment. When done without evaluation, this activates reward systems without reintroducing performance monitoring.

Imagined positive affect engages dopaminergic tone, broadens attention, and relaxes facial and postural muscles. These bodily changes feed back into the nervous system, reinforcing safety signals.

Crucially, this is not about achieving happiness or doing the exercise correctly. The moment success becomes relevant, evaluation returns. The practice works only when outcome is irrelevant.

Error hyperreactivity commonly appears in specific domains. Video games often provoke outsized emotional reactions to loss, because they deliver rapid, frequent error signals without social buffering. Social rejection and criticism trigger deeply evolved threat circuits related to status and belonging. Internal dialogue and imagined conversations repeatedly activate error monitoring without resolution.

Voluntary Suspension of Evaluative Control is not apathy. It is not denial of reality. It is not emotional numbing or escapism. It is not a permanent state. It is time-bounded, voluntary, and reversible. Evaluation returns when needed. The goal is flexibility, not elimination. Pathology arises not from evaluation itself, but from its constant, uncontrollable presence.

Healthy nervous systems switch between modes. They evaluate when action is required and rest when it is not. Many modern individuals have lost this ability. VSEC restores contextual control over evaluation. It reestablishes the capacity to experience moments where nothing is being judged. This capacity is not indulgent. It is necessary.

X. Conclusion: When Nothing Is Wrong

Much of modern psychological suffering arises from error signals firing in the absence of danger. The nervous system cannot heal while alarms are constantly sounding.

Voluntary Suspension of Evaluative Control offers a way to step out of that loop. By allowing periods where nothing is being measured, compared, or optimized, individuals retrain their nervous systems toward proportional response.

Peace does not emerge from perfect performance. It emerges when the brain is allowed, briefly and regularly, to recognize that nothing is wrong.

Jared Edward Reser Ph.D. with ChatGPT 5.2

Leave a comment