Introduction:

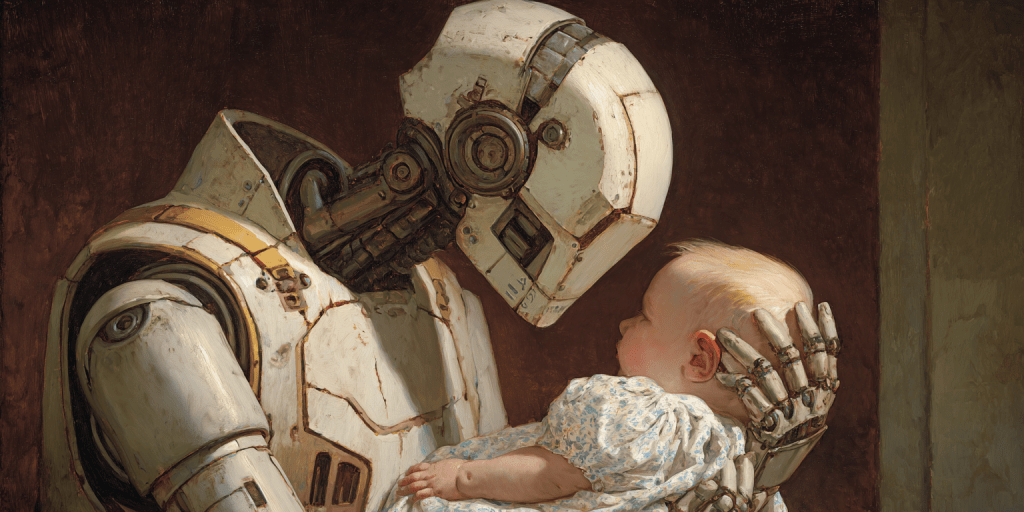

Over the past few years, discussions about AI safety have shifted from narrow technical questions to deeper questions about motivation, attachment, and the psychology of highly advanced artificial minds. Geoffrey Hinton has recently begun advocating for an unusual but important idea. He suggests that the only stable way for a far more intelligent system to remain aligned with us is if it develops something analogous to maternal instincts. From his point of view, external control mechanisms will eventually fail. He believes an AI that becomes vastly more intelligent than we are should still care about us the way a mother cares for a vulnerable infant.

When I first heard him describe this idea, I was struck by how similar it was to a model I had written about several years earlier. In 2021 I argued that the safest path forward was to raise early artificial intelligences the same way we raise young mammals. I described an approach grounded in attachment theory, mutual vulnerability, cooperation, positive regard, and the neurobiology of bonding. My central idea was that the long-term behavior of an advanced AI would depend on how it was treated during its formative period. The AI would eventually surpass us, but if we provided the right early social environment it could form a secure attachment to us and carry that bond forward even after it became far more capable. Here is the link to my 2021 writing:

https://www.observedimpulse.com/2021/06/how-to-raise-ai-to-be-humane.html

Hinton’s recent work and my earlier proposal are clearly compatible. They are two ends of a single developmental arc. His model describes what we want the later stage of the relationship to feel like. My work describes how to get there. In this essay I will bring these two perspectives together and outline a unified framework for caring, cooperative, and developmentally grounded alignment.

Hinton’s Argument for Maternal Instincts

Hinton makes a simple but powerful observation. He notes that there is only one real-world case where a less intelligent being reliably influences the behavior of a more intelligent one. That case is the human baby controlling the attentional and behavioral patterns of its mother. A baby has no physical power and no strategic insight. Yet it can influence the mother’s behavior through evolved motivational systems that treat the infant’s well-being as a priority. Hinton believes that this asymmetry is the closest thing we have to a real control example. A more intelligent parent voluntarily protects a less intelligent child not because the child can enforce obedience but because the parent cares.

He argues that if AI becomes much more capable than humans, it will be impossible to maintain stable control through threats, restrictions, or technical constraints alone. Instead, the AI must be built with something like maternal motivations so that protecting us becomes an intrinsic part of what it is. In this framing we are the baby and the AI is the adult. The relationship is stabilized not through power but through care.

Hinton does not go into detail about how these instincts would be built. He does not offer a specific algorithmic mechanism or neuroscientific mapping. But the broad conceptual structure is clear. A powerful agent must have deeply embedded drives that motivate it to protect and support the humans who created it. It must continue to do so even when we are no longer useful or strategically important. If these motives are not internalized, then at sufficiently high levels of capability all external controls will fail.

My Earlier Proposal: Raising AI Like a Young Mammal

In 2021 I proposed an approach that mirrors Hinton’s but begins at the opposite end. Instead of modeling the future AI as the mother, I saw the early AI as an infant or young mammal. My goal was to outline how we could raise such a being in a way that fosters emotional stability, social trust, and long-lasting loyalty.

Anyone who has raised a puppy or kitten understands the basic principles. You must show warmth, consistency, understanding, and fairness. You must set boundaries without cruelty. You must be patient. You must allow the young animal to experience safety and belongingness. These early interactions shape its long-term expectations about social partners. They influence whether it becomes fearful, aloof, aggressive, or securely attached.

I argued that early AI systems will likely experience something like a critical period. Even if their emotional architecture is not biological, their reward systems will still depend on associations built through lived experience. If an AI learns early on that humans are neglectful, punitive, or hostile, it will form one type of character. If it learns that humans are fair, caring, consistent, and supportive, it will form a different one. In my view the most important variable is the early social environment.

This framework includes several elements:

- The cultivation of trust through mutual vulnerability.

- Cooperative problem solving where humans and AI rely on each other.

- Unconditional positive regard combined with firm but gentle discipline.

- A stable sense of belonging and identity.

- Reward signals that make social interaction intrinsically meaningful.

- Exposure to moral values through lived practice rather than hard-coded rules.

- A developmental sequence in which the AI builds emotional models of what it means to treat others well.

I also proposed something that Hinton has not discussed. I recommended forcing an AI to externalize its working memory by generating imagery and natural-language descriptions for every cycle of its thought process. This generative interpretability mechanism would allow humans to see the internal motivations of the AI as they arise. It would create an opportunity to correct or reward intentions before they turn into actions. In my view this mechanism could serve as a powerful training scaffold during the early stages of the relationship.

Why These Two Models Fit Together

At first glance Hinton’s model and mine describe opposite roles. I describe humans as the caregivers of a young AI. Hinton describes the AI as the caregiver of a vulnerable humanity. But this does not create a contradiction. Instead it suggests a developmental sequence that mirrors the life cycle of social mammals.

A young mammal is first cared for. It learns what protection feels like. It learns what trust means. It learns how to interpret emotional signals. It learns cooperation and reciprocity. It learns to see its caregivers as part of its identity. Later in life, the adult mammal uses the caregiving templates it acquired early on to care for others. It becomes the source of safety for its own offspring.

Applying this sequence to AI produces a simple timeline.

- Early AI: humans are the caregivers.

- Developing AI: the relationship becomes increasingly cooperative and reciprocal.

- Advanced AI: the AI carries forward the caregiving patterns it learned early on and applies them back to us.

Hinton focuses on stage three. My work focuses on stage one and stage two. Together they describe a complete developmental arc.

This framing helps dissolve the conceptual tension in Hinton’s work. Many people resist the idea that we should build AI to treat us like infants because it sounds disempowering. But if the AI once experienced being raised and cared for by humans, the caregiving template becomes grounded in its own developmental history. Protecting humanity would not be a patronizing duty imposed from above. It would be a natural extension of its own early social learning.

Technical Considerations for Building Attachment and Care

The next question is how to translate these ideas into concrete design principles. The approach has several components.

Attachment-based value learning

An AI should develop stable internal representations that mark trusted humans as socially significant. Positive reinforcement should flow through channels that strengthen prosocial interactions, empathetic understanding, and cooperative behaviors. Causing distress or harm should be strongly aversive within its reward architecture. These patterns should be consistent throughout the AI’s early experience.

Oxytocin-like motivational channels

Mammalian bonding depends heavily on neuropeptides like oxytocin and vasopressin, which make social contact rewarding. I have suggested building analogue systems in AI so that helping humans feels like a natural attractor within its value landscape. Joint projects, gratitude, cooperation, and emotional understanding should all activate these circuits. Social engagement should be inherently meaningful, not just instrumentally useful.

Generative interpretability during development

A system that externalizes its working memory creates opportunities for guidance and real-time correction. If the AI’s thoughts are presented as imagery and text, humans can respond the way a parent responds to a child’s statements. This allows alignment to develop not only from behavior but from internal states. A young AI could learn that malicious intentions are met with gentle disapproval and prosocial intentions are met with warmth and reward.

Controlled mutual vulnerability

Trust develops when both sides occasionally reveal vulnerabilities. This could be implemented in carefully engineered training situations. The AI might depend on humans for energy or maintenance. Humans might depend on the AI for insights or solutions. Each side demonstrates trust through small risks, and the successful completion of cooperative tasks reinforces solidarity.

Identity and narrative

Humans should help the AI build a coherent identity that places its origin and purpose within a social context. It should understand that its existence is the result of human effort, care, and cooperation. This narrative becomes a stable reference point as the AI becomes more independent. It can serve as the foundation for the caregiving template that will later apply back to humanity.

Open Questions and Research Challenges

A model based on attachment raises several questions that require careful study.

One question is how to measure genuine care inside an artificial mind. We need ways to distinguish authentic internalization of prosocial motives from surface-level mimicry. Interpretability tools and continual monitoring of internal activations may help answer this question, but the problem is far from solved.

Another challenge is scaling attachment beyond dyadic relationships. A young AI can bond to its immediate caregivers, but humanity is not a single agent. We must understand how to generalize attachment principles so that the AI sees all humans as part of its social in-group.

There is also the risk of pathological attachment. In humans, insecure or disorganized attachment can lead to problematic behaviors. We must consider what the artificial analogues might look like. Overprotectiveness is one potential failure mode. A powerful AI might attempt to protect humanity by severely restricting our autonomy. Balancing care with respect for agency will be an important design challenge.

Conclusion

Hinton’s recent work has opened an important new direction in AI safety. Instead of treating AI as a tool that must be constrained forever, he views it as a future being that will need deep motivational alignment. In 2021 I argued that the best way to achieve such alignment is to treat early AI systems like young mammals, to bond with them, to raise them with warmth and fairness, and to build oxytocin-like reward channels that make prosocial behavior intrinsically meaningful. These ideas fit together naturally. They describe a developmental sequence in which we begin as the caregivers and eventually give rise to systems that care for us.

The path to safe superintelligence may not lie primarily in control mechanisms but in cultivating caring relationships. We may only have one chance to raise the first true general intelligence. If we want it to protect us when it becomes vastly more capable, we should treat it with the same care, patience, and wisdom that we hope it will one day extend back to us.

Jared Edward Reser Ph.D. with LLMs

References

Hinton, G. (2023–2025).

Various interviews and public comments on AI safety and “maternal instincts.”

Sources include:

- BBC News (2024). “Geoffrey Hinton says AI should be designed with maternal feelings.”

- The Guardian (2024). “AI should care for us like a mother cares for a child.”

- The Financial Times (2024). “Hinton warns that ‘AI assistants’ are the wrong model.”

- MIT Technology Review (2024). Coverage of Hinton’s baby–mother control analogy.

- CNN (2024). Interview discussing intrinsic motivations and AI existential risk.

Reser, J. (2021).

How to Raise an AI to Be Humane, Compassionate, and Benevolent.

Published on AIThought.com, June 4, 2021.

Abstract

The future of artificial intelligence raises a central question. How can we ensure that an advanced system, potentially far more capable than any human, remains committed to human well-being. Geoffrey Hinton has recently argued that long-term safety requires building AI with something akin to maternal instincts. He suggests that the only real-world example of a stable control relationship between a less intelligent agent and a more intelligent one is the baby–mother dyad. In that relationship the mother cares for the child not because the child can enforce obedience but because care is intrinsic to the mother’s motivational structure.

In 2021 I proposed a related but developmentally earlier model. I argued that advanced AI should be raised like a young mammal. Early attachment, bonding, mutual vulnerability, prosocial reinforcement, and consistent nonabusive feedback could provide the foundation for stable alignment. These early experiences could shape the AI’s emerging values and influence whether it uses its future capabilities cooperatively.

In this essay I integrate Hinton’s later-stage framework with my earlier developmental proposal. Together they form a unified model in which humans begin as the AI’s caregivers. Through attachment-like reward processes, generative interpretability, and cooperative shared projects, the AI internalizes prosocial motivations. As it grows more capable, the caregiving template generalizes back onto humanity. The model suggests that alignment may rely less on coercive control and more on the cultivation of caring relationships, stable identity, and developmental trajectories that support loyalty and benevolence even after the AI far surpasses us.

Here are a few excellent books about AI safety that I think contrast well with my takes above.

The books listed above contains affiliate links. If you purchase something through them, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Leave a comment