Jared Edward Reser Ph.D.

Abstract

Brains are metabolically expensive organs, and complex cognition is not automatically adaptive. This essay develops a return on investment framework built around two linked constructs introduced and motivated in Reser (2006): meme utility and cognitive noise. Meme utility is defined as the survival advantage conferred by the acquisition and use of transferable behavioral information. Cognitive noise is defined as cognition that directs future behavior without producing a survival advantage. The central claim is that the adaptive value of cognition depends strongly on the utility of socially transmitted behavioral structure. When meme utility is high, cognition is guided by externally validated action policies that constrain drift and reduce wasted inference. When meme utility is low, especially under low parental instruction or low quality social learning conditions, cognition can become unmoored from ecological payoff and expand into cognitive noise. To formalize these relationships, I introduce a cognitive balance sheet that separates cognitive yield, cognitive noise, and cognitive overhead, and treat meme utility as a major input to cognitive yield. I then argue that cognition and meme utility are mutually dependent: cognition is required to acquire, retain, retrieve, and apply memes, while memes provide constraint and calibration that make cognition profitable.

1. Introduction

Cognition is often treated as a generic advantage, as if more intelligence must always increase fitness. A neuroecological view suggests a more conditional relationship. The brain is costly tissue, and the behaviors it enables can either enhance survival and reproduction or divert time, attention, and energy away from them. The adaptive question is therefore not whether cognition exists, but when cognition pays.

In this framework, the payoff of cognition depends on whether cognition is supplied with reliable guidance that connects internal models to ecological outcomes. For many encephalized animals, a major source of such guidance is socially transmitted behavioral information. In the terms used here, that guidance is delivered through memes, and its payoff is captured by meme utility (Reser, 2006).

The complementary risk is that cognition can generate behavior guiding internal structures that are not fitness enhancing. This includes irrelevant or fallacious conceptualizations and forms of extraneous thinking that interfere with vigilance and ecological performance (Reser, 2006).

This essay advances two connected aims. First, it provides clear formal definitions of cognitive noise and meme utility as outcome anchored constructs (Reser, 2006). Second, it introduces a simple accounting device, the cognitive balance sheet, to express cognition as a return on investment problem rather than a generic virtue.

2. Core definitions

2.1 Cognitive noise

Cognitive noise refers to thoughts, conceptualizations, or cognitions that influence future behavior without producing a survival advantage (Reser, 2006). The definition is intentionally outcome anchored. It does not require that the cognition be conscious, verbal, or abstract. It includes any internally generated control structure, whether it takes the form of a learned association, a hypothesis about the world, a habitual interpretation, or a preoccupation that alters attention and choice.

Two clarifications are essential.

First, cognitive noise is not synonymous with mental variability. Some variability is adaptive exploration. Cognitive noise is the subset of cognition that has behavioral consequences but does not improve fitness relevant outcomes in the organism’s ecological setting.

Second, cognitive noise is expected to be context dependent. A cognition that is noise in one niche can become useful in another. This is one reason to keep the definition tied to survival advantage rather than to phenomenology.

The concept is motivated by a developmental and life history observation: if an organism’s intelligence were increased without a corresponding increase in parental instruction or ecological scaffolding, fitness could be hindered by a greater tendency toward irrelevant or fallacious conceptualizations (Reser, 2006). Under deprivation, a highly encephalized animal may misapply analysis and construct mental systematizations that do not facilitate threat avoidance, feeding, or reproduction (Reser, 2006).

2.2 Meme utility

Meme utility is the measure of the survival advantage that the utilization of memes provides for an individual animal, where memes are units of behavioral information transferable between animals (Reser, 2006). Meme utility is therefore defined as an increment in fitness relevant performance attributable to the acquisition and use of socially transmitted behavioral structure.

This definition is compatible with a broad range of cultural evolutionary and social learning approaches, but it emphasizes an explicitly ecological criterion: the meme matters insofar as it improves survival and reproduction in context.

A key implication is comparative. Meme utility is expected to be high in many altricial, K selected animals for whom parental guidance and social learning are central, and lower in more precocial, r selected animals that have less need for extended instruction (Reser, 2006). The definition also invites a developmental prediction: maternal deprivation should predict a decrement in meme utility, reducing the realized payoff of culture mediated learning (Reser, 2006).

3. The cognitive balance sheet

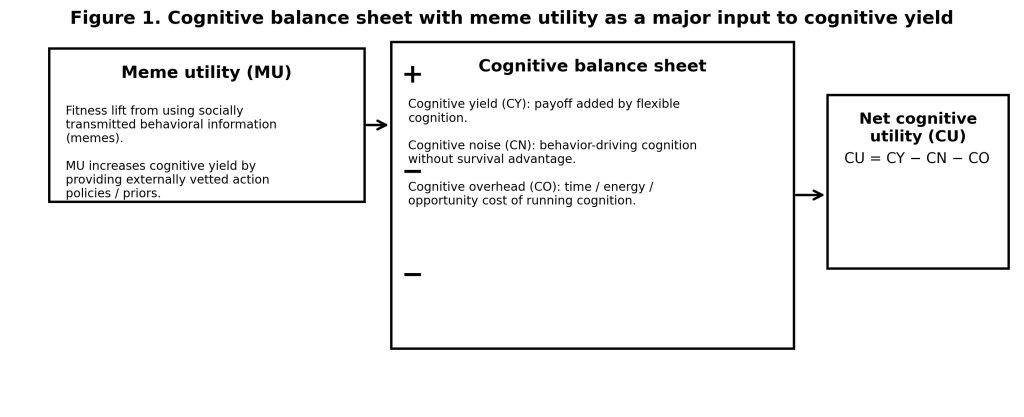

The two concepts above become most useful when embedded in a simple accounting framework. Figure 1 presents cognition as a balance sheet with three terms.

Cognitive yield is the fitness relevant payoff added by flexible cognition. It includes improved decision making, better ecological prediction, refined motor sequences, and strategic social behavior, wherever these translate into survival and reproduction.

Cognitive noise is the portion of cognition that influences behavior without improving survival advantage, including cognition that diverts attention or generates maladaptive conceptualizations (Reser, 2006).

Cognitive overhead is the cost of cognition, including metabolic cost and opportunity cost. A salient example is vigilance cost, where extraneous thinking can interfere with an animal’s ability to remain vigilant in contexts where vigilance is strongly fitness relevant (Reser, 2006).

Net cognitive utility can then be expressed as:

CU = CY − CN − CO

In this framing, meme utility functions as a major input to cognitive yield because it supplies externally validated action structure that reduces the need for costly trial and error and constrains the space of internally generated models.

The balance sheet also motivates directional hypotheses proposed in Reser (2006), including the idea that cognitive noise should increase with encephalization, decrease with parental investment, and vary inversely with reproductive success. These are not treated here as settled laws. They are treated as testable implications of the balance sheet logic.

4. How meme utility and cognitive utility couple

The tightest link between these constructs is that meme utility is not independent of cognition, and cognitive utility is not independent of memes. They are coupled in both directions.

4.1 Cognition is required to realize meme utility

For meme utility to be nonzero, an organism must perform at least four cognitive operations.

It must acquire the meme, meaning it must parse another’s behavior into a learnable procedure. It must retain the meme in memory in a form that remains usable. It must recognize applicability, meaning it must detect when a current situation matches the conditions under which the stored behavior should be deployed. Finally, it must execute the behavior in a way that fits the constraints of the current ecological context.

These steps imply a practical point that will matter later for operationalization. An organism can possess abundant cultural information in its environment and still exhibit low realized meme utility if any of these gates fail, especially applicability recognition. A large store of memes does not guarantee high payoff if retrieval is poorly indexed or contextual triggering is unreliable.

4.2 Memes discipline cognition and reduce cognitive noise

The reverse direction is equally important. The underlying idea is that memes provide constraint. They limit the degree to which cognition must invent action policies from scratch, and they bias cognition toward behaviors already filtered by prior ecological success (Reser, 2006).

When memes are effective, they can increase cognitive yield while simultaneously reducing cognitive noise. The same cognitive capacity that can generate irrelevant or fallacious conceptualizations can instead be anchored by externally vetted behavioral information and deployed toward payoffs that matter.

4.3 Low meme utility as a condition for cognitive drift

When meme utility is low, the balance sheet can invert. A highly encephalized animal deprived of parental instruction may misapply mental analysis and construct conceptualizations that do not facilitate threat avoidance, feeding, or reproduction. It may also engage in extraneous thinking that interferes with vigilance (Reser, 2006). Under these conditions, cognitive noise rises not because the organism lacks cognitive capacity, but because cognitive capacity is underconstrained by useful social information and by reliable calibration.

This sets up the central theoretical landscape for the remainder of the paper. High cognition can be either profitable or wasteful. Meme utility is one of the most important variables that determines which regime an organism occupies, because it determines whether cognition is supplied with socially grounded structure that makes its costs worth paying.

5. Dual-timescale return on investment

The balance sheet framing implies that cognition is optimized on at least two timescales. On the evolutionary timescale, selection shapes species typical brain investment, life history, and developmental schedules so that, on average, cognitive yield exceeds cognitive noise and cognitive overhead in the environments that mattered most. On the individual timescale, phenotypic plasticity calibrates how heavily an organism relies on costly cognition and socially transmitted information, conditional on early life cues and ongoing ecological feedback.

At the population level, the relevant question is whether an encephalized, plastic strategy is worth its energetic and developmental cost. Reser’s core proposal is that the payoff of encephalization depends strongly on the availability and effectiveness of memes, which are treated as transferable units of behavioral information (Reser, 2006). Under this view, selection does not merely favor bigger brains. It favors bigger brains in niches where social learning and parental instruction can reliably deliver high meme utility, thereby raising cognitive yield and reducing the need for costly trial and error.

At the individual level, the organism effectively faces a conditional investment problem. The brain’s structural capacity is largely fixed by genotype and species history, but the brain’s operating policy is plastic. It can shift its allocation of attention, planning depth, trust in informants, and reliance on social versus individual learning in response to cues that predict the likely returns of memes and the likely costs of error. This point is crucial for your theoretical landscape because it explains how the same encephalized architecture can express very different balance sheets across developmental contexts. Under conditions that forecast reliable social scaffolding, the organism should invest in deeper learning, longer horizon planning, and stronger reliance on socially derived priors. Under conditions that forecast unreliable instruction or high volatility, the organism may downshift reliance on socially transmitted structure, increase vigilance, and favor short horizon heuristics. In your language, plasticity can regulate realized meme utility, and through it can regulate the expansion or suppression of cognitive noise (Reser, 2006).

This dual-timescale view also clarifies a subtle but important claim. Cognitive noise is not merely a defect. It can be interpreted as what a high capacity inference system produces when calibration is weak, guidance is unreliable, or payoff is delayed and ambiguous. In those regimes, internal model construction can proliferate faster than it is corrected by ecological outcomes.

6. Companion variables that make the framework testable

Meme utility and cognitive noise can be treated as headline constructs, but they become scientifically useful only if the mechanisms that modulate them can be measured. The following variables are intended as a minimal set. They specify where meme utility is gained or lost, and where cognitive noise tends to grow.

Meme fidelity is the integrity of a meme across transmission. High fidelity means the action relevant structure arrives intact. Low fidelity means distortion, omission, or performative copying erodes the utility of the transmitted behavior.

Meme accessibility is the probability that an individual actually encounters relevant behavioral information in its social environment. A population can contain valuable memes, but an individual’s realized meme utility can be low if it does not reliably encounter skilled models at the right times.

Meme uptake efficiency is the conversion rate from exposure to durable, correctly deployable behavior. This is where parental instruction and developmental scaffolding matter most. If uptake per exposure is low, the organism must spend more time in trial and error, or must rely more heavily on internal invention, both of which can inflate cognitive overhead and cognitive noise (Reser, 2006).

Meme trust calibration is the organism’s ability to weight social information by credibility and payoff. Poor calibration yields two distinct failures. Undertrust causes the organism to reject useful memes, lowering realized meme utility. Overtrust causes the organism to adopt low payoff or harmful memes, which reduces cognitive yield and can increase cognitive noise through misdirected internal model formation.

Ecological corrective pressure is how strongly and quickly the environment corrects maladaptive models and behaviors. In tight feedback environments, errors are rapidly punished or corrected. In permissive or ambiguous environments, wrong models can persist because consequences are delayed, stochastic, or weak. Low ecological corrective pressure is a direct recipe for cognitive noise because it reduces the rate at which unproductive cognitions are extinguished.

Instinct reserve is the retained capacity to fall back on robust, low compute, species typical control policies when meme guided cognition fails. This variable matters most when meme utility is low or when ecological corrective pressure is low. It also allows the framework to cover precocial species cleanly. Precocial animals can still have cognitive noise, but they may rely more on instinct reserve to limit the damage of mislearned associations.

These variables function together. Meme utility is not a single dial. It is an emergent quantity that depends on fidelity, accessibility, uptake, trust calibration, and the ecology’s corrective pressure. Likewise, cognitive noise is not merely “too many thoughts.” It is the outcome of an inference system with substantial representational degrees of freedom operating in a regime where guidance and correction are insufficient.

Comparative neuroecology across vertebrates

The vocabulary developed here becomes most illuminating when mapped onto real phylogenetic and ecological differences among vertebrates. The core claim is not that any lineage “has” or “lacks” meme utility or cognitive noise. The claim is that lineages differ in (i) the degree to which survival depends on socially transmitted behavioral information, (ii) the developmental and social machinery that supports transmission, and (iii) the ecological feedback structure that corrects maladaptive cognition. These differences should predict systematic variation in realized meme utility, cognitive overhead, and the expression of cognitive noise (Reser, 2006).

Fish

Many fish species are highly precocial, with relatively strong instinct reserve and comparatively limited parental scaffolding. This tends to constrain the niche in which memes can dominate survival outcomes. Still, fish exhibit substantial social learning in contexts such as foraging, predator avoidance, and migration routes. In the present framework, this means meme utility can be locally high even when extended parental investment is low, provided meme accessibility is high (dense shoaling, frequent opportunities to observe conspecifics) and ecological corrective pressure is strong (rapid payoffs or penalties in predator rich environments). Cognitive noise in fish should often take the form of overgeneralized threat associations or persistent attraction to non-causal cues, rather than elaborate conceptual drift. In short, fish can exhibit cognitive noise, but the phenotype is expected to be dominated by miscalibrated associative structure rather than long-horizon interpretive narratives.

Reptiles

Most reptiles are also relatively precocial compared with birds and many mammals, and many have limited teaching-like behavior. This suggests a general shift toward higher instinct reserve and lower dependence on socially transmitted procedures for core survival tasks. Meme utility in reptiles may therefore be more specialized, arising in niches where social proximity is stable and repeated observation is possible, such as aggregation sites, territorial systems, or species with extended parental attendance. When meme utility is low, the framework predicts that cognitive overhead and cognitive noise are kept in check partly by reliance on robust innate action programs. When meme utility is nontrivial, it should be most visible in the efficiency gains of social information use, such as improved predator recognition or foraging site selection, rather than in complex cultural repertoires.

Non-avian dinosaurs

Any application to non-avian dinosaurs must be explicitly labeled as inference rather than direct observation. We cannot measure meme utility or cognitive noise directly, but we can reason from proxies that matter in this framework: encephalization relative to body size, evidence consistent with sociality, and evidence consistent with parental care or prolonged juvenile association. Fossil evidence for nesting behavior and, in some taxa, plausible parental attendance suggests that at least some dinosaur lineages created developmental contexts where meme accessibility and uptake could plausibly be elevated. If that is correct, then certain dinosaurs may have occupied a regime where meme utility was meaningful, especially for behaviors like group movement, site fidelity, or predator avoidance. At the same time, if many dinosaurs were relatively precocial with strong instinct reserve, the predicted form of cognitive noise would be closer to the fish and reptile pattern: miscalibrated associations and maladaptive persistence, not prolonged abstract rumination. The key point is that the framework yields a set of comparative questions that can be tied to anatomical and life history proxies, even when direct behavioral data are unavailable.

Birds

Birds provide a strong test case because many lineages combine high encephalization, intensive social learning, and rich vocal or motor traditions. In birds, meme utility can be high because meme fidelity can be maintained through repeated practice, frequent observation, and in some cases structured tutoring-like exposure, as in song learning. When memes are embedded in stable social networks, meme accessibility is high and trust calibration can become highly selective, with learners preferentially copying high quality models. This should raise cognitive yield and reduce cognitive noise by constraining behavioral search. At the same time, birds span a wide altricial to precocial spectrum. Highly precocial birds should show a lower dependence on socially acquired behavioral structure for basic survival, while still supporting specialized high utility memes where social learning is unavoidable, such as navigation routes or complex foraging strategies. The framework predicts that where birds are strongly altricial and socially tutored, cognitive noise should be lower relative to cognitive yield because the developmental pipeline supplies reliable constraints early.

Mammals

Mammals, especially those with extended juvenile periods, are a natural home for this framework because parental investment and alloparenting can strongly elevate meme uptake efficiency. In many mammals, meme utility should be high precisely because juveniles have long periods of protected learning, repeated exposure to skilled models, and social mechanisms that permit selective trust. This is the regime in which the cognitive balance sheet can be strongly positive: high cognitive overhead is tolerable because culturally mediated constraint increases cognitive yield and suppresses cognitive noise. Mammals also illustrate how ecological corrective pressure interacts with social learning. In harsh environments with rapid, unforgiving consequences, strong corrective pressure can reduce the persistence of maladaptive models. In buffered or ambiguous environments, incorrect strategies can persist longer, raising the opportunity for cognitive noise, unless social scaffolding provides strong constraint.

Primates

Primates are the clearest case where the coupling between cognition and meme utility becomes central rather than peripheral. Many primates combine high representational capacity with prolonged dependence on social learning, complex social inference, and extended developmental plasticity. In this regime, meme utility is not only about acquiring procedures, but also about learning social norms, alliance management, tool use traditions, and context-sensitive decision rules. The gating role you emphasized earlier becomes decisive here. High meme utility requires not just acquiring and retaining memes, but recognizing applicability and retrieving the right behavioral policy at the right moment. When this gating works, cognition becomes highly profitable and cognitive noise is contained by culturally reinforced constraints. When the developmental or social environment disrupts scaffolding, trust calibration, or feedback structure, the same representational freedom that supports primate intelligence can expand into cognitive noise, including persistent low payoff interpretive models that nevertheless guide future behavior (Reser, 2006).

A unifying comparative prediction

Across these taxa, the framework predicts a shift from predominantly instinct-buffered cognition toward culturally constrained cognition as encephalization and developmental dependence increase. In lineages where survival depends heavily on socially transmitted behavioral structure, selection can tolerate high cognitive overhead because meme utility raises cognitive yield and reduces cognitive noise. In lineages where survival depends less on socially transmitted procedures, instinct reserve limits both the benefits and the hazards of flexible cognition, and cognitive noise should express more as miscalibrated associations than as expansive conceptual drift. This is the comparative backbone of the theory: cognitive noise and meme utility are not species labels, but ecological outcomes of how brains, development, social transmission, and environmental correction interact.

Conceptual drift in humans

A useful way to extend the framework is to name a specifically human expression of cognitive noise. I will call this conceptual drift. Conceptual drift is the tendency for a high capacity cognitive system to generate and elaborate interpretive models that steer attention and behavior, yet fail to converge on improved ecological payoff. It is not mere distraction. It is structured meaning making that becomes insufficiently constrained by calibration. In the language of this paper, conceptual drift is one of the most important ways that cognitive noise manifests in humans.

Humans are especially vulnerable to conceptual drift because we sit at an extreme point in the parameter space described above. We have high representational freedom, meaning we can construct causal narratives, counterfactual worlds, social simulations, and self models with enormous combinatorial breadth. We also live in environments where ecological corrective pressure is often weak for the beliefs that matter most to us. Many of our most emotionally salient models concern social evaluation, identity, status, reputational risk, long horizon futures, and abstract moral or political commitments. In these domains, feedback is delayed, ambiguous, and socially mediated. When correction is weak, maladaptive models can persist for long periods, which gives drift room to accumulate. Finally, modern humans experience extremely high meme accessibility, but the utility of accessible information is uneven. When accessibility rises faster than utility, cognition can be flooded with inputs that stimulate model construction without reliably improving decision quality.

Conceptual drift has a characteristic dynamic profile. It proliferates interpretations. The system produces explanatory frames quickly, often in response to uncertainty, threat, or social ambiguity. It becomes self referential. The models begin to explain the model builder, which can create recursive loops in which the person constructs theories about why they are thinking what they are thinking. It is often sticky. Even when a model fails to improve outcomes, it persists because it is emotionally charged, identity relevant, or socially reinforced. Crucially, drift is not inert. It biases action selection by shifting what the person attends to, avoids, rehearses, or anticipates. For this reason, conceptual drift should be treated as a behavioral construct rather than as a purely introspective one.

Within the present framework, conceptual drift becomes more likely when three conditions co-occur. The first is low meme trust calibration, where the person weights social information by prestige, emotional resonance, or group alignment rather than by payoff tracking. The second is low meme uptake efficiency for high yield content, meaning that the memes that would genuinely increase cognitive yield do not take root due to weak scaffolding, weak mentorship, or poor learning conditions. The third is low ecological corrective pressure in the domain that dominates the person’s cognition. When these conditions hold, representational freedom tends to expand into cognitive noise, and conceptual drift becomes the predictable regime.

Conceptual drift is especially pronounced in social cognition because humans live inside other minds. A large fraction of our decision making concerns what other people believe, intend, and value. Social inference is a domain with unusually weak ground truth. Intentions are not directly observable, feedback is noisy, and social incentives sometimes reward beliefs that signal loyalty rather than beliefs that track reality. This creates a chronic decoupling between coherence and payoff. The person can accumulate elaborate models that intensify emotion and steer behavior without improving relationships, competence, or safety. In balance sheet terms, cognitive overhead rises and cognitive yield does not.

This concept also requires a clear boundary condition so it is not confused with adaptive exploration or creativity. Exploration is constrained by a search objective. It generates hypotheses, tests them against outcomes, and prunes aggressively. Conceptual drift is exploration without pruning. The hypothesis space expands, but correction is weak, and the system begins to optimize for internal coherence, affect regulation, or social signaling rather than for payoff. One operational consequence is that exploration should improve performance on repeated trials, while drift should not, even when cognitive effort is high.

Conceptual drift can be operationalized in humans without relying on introspective report. One signature is low convergence: across repeated decisions, the person continues to generate new rationales without stabilizing on a strategy that improves outcomes. A second signature is high narrative production paired with low performance gain: the person can articulate rich theories about a domain while objective performance remains flat. A third signature is overfitting to noise: explanations track spurious correlations and shift rapidly with recent events. A fourth signature is persistence under disconfirmation: when outcomes contradict the model, the model is preserved by adding auxiliary assumptions rather than being pruned. A fifth signature is transfer failure: the elaborated model fails to generalize to closely related contexts where it should apply if it were capturing causal structure.

Conceptual drift therefore provides a concrete, human centered bridge between meme utility and cognitive noise. When high utility cultural constraints are available and well learned, cognition becomes disciplined and convergent. When those constraints are absent, corrupted, or drowned in low utility inputs, cognition becomes freer running, and conceptual drift becomes an expected consequence of a powerful model building system operating under weak calibration.

7. Formalization sketch

The balance sheet can be expressed without heavy mathematics, but it helps to define the constructs in a way that can be estimated from data.

Let denote a fitness proxy appropriate to the organism and task: calories acquired, injuries avoided, offspring survival, predator detection accuracy, or any outcome that plausibly maps onto survival advantage. Let denote an action policy.

Define a baseline policy as the best available low compute strategy for the organism in a given task family. This baseline can be operationalized as performance under cognitive constraint, or as a heuristic controller derived from observed behavior.

Define a cognition enabled policy as behavior when the organism can deploy its full cognitive apparatus.

Cognitive yield can then be operationalized as:

Cognitive noise is the component of cognition that changes behavior without survival advantage. Operationally, it can be defined as the expected decrement attributable to cognition driven deviations that do not improve payoff:

This definition encodes the idea that cognition becomes “noise” to the extent that it reduces fitness proxy outcomes relative to a baseline.

Cognitive overhead is the cost of cognition, which can be represented as time, effort, or opportunity cost terms that do not appear in directly but nonetheless constrain fitness. If desired, overhead can be folded into an augmented payoff function that penalizes time and energy.

Meme utility can be defined causally as the increment in expected payoff attributable to meme acquisition and use:

Here is the policy after exposure to a demonstrator or cultural instruction, and is the matched policy without that exposure.

A useful refinement is to decompose realized meme utility into gates. This matches your earlier point that memes can be present, but still fail to pay.

Let be encounter, be learning, be retention, be applicability detection and retrieval, and be execution competence. Then the probability that a meme actually improves behavior in a relevant episode is approximately:

Meme utility is then the payoff lift conditional on effective use, multiplied by this effective use probability. This decomposition immediately reveals where interventions, deprivation, or ecological changes can reduce realized meme utility. It also shows where cognitive noise can enter. Mislearning, misindexing, misretrieval, and misexecution can all produce behavior guided by internal content that fails to improve payoff.

8. Operationalization paradigms

To make this framework credible, the essay should offer paradigms that estimate meme utility and cognitive noise from the same dataset.

One family of designs uses a demonstrator manipulation. Subjects are assigned either to a demonstrator condition, where they can observe a skilled model performing a task, or to a no demonstrator condition, where they must learn individually. Meme utility is the performance delta between these conditions, ideally measured across multiple tasks that differ in ecological structure. Meme fidelity can be estimated by asking learners to reproduce the demonstrated procedure and scoring deviations. Meme uptake efficiency is the performance gain per unit exposure, and retention is measured by delayed testing.

A second family of designs measures applicability detection explicitly. After a meme is learned, the subject is placed into a set of contexts, some of which match the learned meme’s applicability conditions and some of which do not. The key dependent variable is not only whether the meme is recalled, but whether it is recalled selectively in the contexts where it pays. This is the cleanest way to operationalize the gating role you emphasized. It distinguishes “having the meme” from “knowing when the meme applies.”

A third family of designs estimates cognitive noise via spurious rule formation and maladaptive persistence. Use task environments that contain tempting but non causal correlations, or environments that change contingencies after initial learning. Cognitive noise can be indexed by the extent to which subjects construct and persist in behavior guiding models that do not improve payoff, especially when those models create opportunity costs such as slower responding or reduced vigilance. For animals, this can be done with foraging tasks, predator cue discrimination, or detour and reversal learning setups, as long as outcomes map plausibly onto survival advantage.

Ecological corrective pressure can be manipulated directly by varying feedback delay, ambiguity, and stochasticity. When correction is delayed or noisy, wrong models should persist longer. The framework predicts that low ecological corrective pressure increases cognitive noise, and it reduces realized meme utility because it weakens the calibration signal that normally tunes both individual learning and the effective deployment of socially acquired information.

9. Comparative and developmental predictions

The framework generates a small set of strong predictions that can be stated without overreach.

First, meme utility should be higher in lineages and niches where social learning is central to fitness, and lower where behavior is largely canalized and precocial. This does not imply that precocial animals have no cognitive noise. It implies that the dominant sources of cognitive noise differ, and that instinct reserve may reduce its impact.

Second, within a species, reduced parental instruction or unstable social scaffolding should lower meme uptake efficiency and meme trust calibration, thereby lowering realized meme utility. Under those conditions, cognitive noise should rise, either through spurious model formation or through attention allocation that reduces vigilance and immediate ecological performance. This is the developmental core of the proposal in Reser (2006), which ties low parental investment to increased fallacious conceptualization risk and to reduced fitness.

Third, ecological corrective pressure should modulate both constructs. In environments with strong corrective pressure, cognitive noise should be kept in check by rapid feedback, and meme utility should be amplified because correct procedures are quickly confirmed and misapplications are quickly extinguished. In environments with weak corrective pressure, cognitive noise should persist, and meme utility should be more fragile because the learner receives fewer reliable signals that align social information with actual payoff.

Finally, the balance sheet suggests an interaction. The costs of cognitive noise should be largest in organisms with high cognitive capacity and low guidance. In such cases, representational freedom is high, but the constraints that normally convert it into yield are weak.

10. Relationship to adjacent literatures

This framework is intended to translate between fields rather than compete with them.

In cultural evolution and social learning research, meme utility corresponds to the payoff side of social transmission, while meme fidelity and accessibility correspond to transmission integrity and exposure. Your contribution is to treat these cultural variables as direct determinants of the profitability of cognition, not merely as descriptive features of culture.

In developmental science, the variables map naturally onto scaffolding, teaching, and selective trust. Meme uptake efficiency is an explicit bridge to pedagogical scaffolding. Meme trust calibration aligns with selective social learning and epistemic vigilance. The distinctive move here is to place these within an ROI framework that predicts when cognition becomes wasteful because it lacks reliable external calibration.

In decision theory and cognitive control, cognitive overhead corresponds to the cost of computation and the opportunity cost of effort. Cognitive yield corresponds to the value added by model based control and planning. Cognitive noise corresponds to a specific failure mode of costly computation, where the system spends resources generating behavior guiding structure that does not improve payoff.

In reinforcement learning and behavioral ecology, ecological corrective pressure is closely related to feedback density and environmental volatility. It specifies how quickly behavior is shaped by consequences, and therefore how quickly maladaptive internal models are extinguished.

11. Transition

The first part of this artcile established the two anchor constructs and the balance sheet. The second part has now specified the dual timescale ROI logic, the minimal companion variables, a formal decomposition that can be estimated from data, and the core predictions. The remaining work is to address boundary conditions and alternative interpretations carefully. The most important is to distinguish cognitive noise from exploration and long horizon cognition whose payoff is delayed. Another is to distinguish low meme utility from maladaptive meme content. These issues will be handled explicitly, together with a concise conclusion that lists the few strongest testable claims.

12. Boundary conditions, clarifications, and measurement cautions

The framework hinges on an outcome anchored distinction between cognition that improves fitness relevant performance and cognition that does not. That distinction is useful, but it requires careful handling in at least four cases.

First, not all cognition that lacks immediate payoff is noise. Exploration, play, and hypothesis generation can yield delayed benefits, especially in variable environments. A cognition can therefore appear nonproductive within a short observational window while still being adaptive across longer horizons. The practical implication is that any operationalization of cognitive noise must specify the timescale of payoff. The “survival advantage” criterion should be understood as advantage given the ecological horizon that matters for the organism’s life history. This is a definitional refinement rather than a retreat from the construct.

Second, cognitive noise is context dependent. A conceptualization that is maladaptive in one niche can become adaptive in another. That is not a defect of the framework. It is a reminder that cognition is always an interaction between internal models and external structure. In empirical work, this implies that cognitive noise should not be treated as a stable trait in isolation. It should be treated as a trait by environment interaction, with ecological corrective pressure acting as a key moderator.

Third, the cognitive balance sheet depends on what counts as a baseline policy. In formal terms, cognitive yield and cognitive noise are defined relative to some comparator strategy. In practice, the baseline can be operationalized as performance under cognitive constraint, or as the best available heuristic controller for a task family. Different baselines can shift numerical estimates of yield and noise. The remedy is not to avoid quantification, but to be explicit about the baseline and to test robustness across multiple plausible baselines.

Fourth, the construct of cognitive noise should not be conflated with psychopathology. Many clinical categories are defined by distress or dysfunction in modern contexts, not by fitness effects in ancestral ecologies. The framework can generate hypotheses about how certain cognitive phenotypes might emerge under low meme utility or weak calibration, but it should not be used to label disorders as adaptations. At most, it offers a structured way to ask whether a given cognitive pattern reflects a profitable or unprofitable regime of cognition, conditional on development and ecology (Reser, 2006).

13. Alternative explanations and competing interpretations

Several alternative explanations can mimic the empirical signature that this framework predicts. An academic essay should anticipate them explicitly.

One alternative is that low realized meme utility reflects poor meme content rather than failure of acquisition or applicability detection. In other words, the issue may be that the memes are maladaptive in the current niche, not that the organism cannot learn or apply them. This motivates a useful distinction between low meme utility due to low fidelity, low accessibility, low uptake, or poor trust calibration, versus low meme utility because the transmitted behavior is itself low payoff. The latter case is not a failure of cognition. It is a failure of the cultural information stream to provide useful constraint.

A second alternative is ecological mismatch. Even high quality memes can become low utility when environmental structure changes. A meme that was adaptive under one set of predator pressures, foraging demands, or social incentives can become maladaptive under another. In such cases, increased cognitive noise may reflect a transitional period of model updating, not stable drift. This again emphasizes the importance of ecological corrective pressure. If correction is weak or delayed, mismatch driven maladaptive models can persist longer.

A third alternative is reverse causality. Low cognitive performance can itself reduce access to skilled models, reduce trust calibration, and reduce retention. This can make meme utility appear low as a downstream consequence of cognitive constraints rather than as an upstream driver. The best empirical response is experimental. Designs that randomize exposure to demonstrators and manipulate feedback structure can separate causal pathways by making access and corrective pressure exogenous.

A fourth alternative concerns the meaning of “survival advantage” in humans. In modern environments, proxies such as income, education, or social status only partially map onto biological fitness. The framework remains usable, but it forces an explicit choice of outcome variable. In humans, it may be more defensible to operationalize payoff in narrower ecological terms such as hazard avoidance, resource acquisition efficiency, or decision accuracy under time pressure, rather than attempting to infer fitness directly.

These alternatives do not weaken the framework. They clarify what the framework is claiming. The claim is not that cognition always becomes noise under deprivation, nor that memes are always beneficial. The claim is that cognition’s profitability depends on whether social information provides reliable constraint and calibration, and that several distinct failure modes can reduce realized meme utility and inflate cognitive noise (Reser, 2006).

14. Modern mismatch and extensions

A cautious but important extension concerns modern informational environments. The framework distinguishes meme accessibility from meme utility. Modern humans often experience unprecedented accessibility, but the utility of that information can be unstable. In many settings, the informational stream is optimized for salience, social signaling, or engagement rather than for ecological payoff. Under such conditions, high exposure can coexist with low realized utility.

This is precisely the regime that the balance sheet warns about. If the stream of socially transmitted content increases cognitive engagement without delivering reliable, payoff aligned constraint, then cognitive overhead increases and cognitive noise can expand. Two forces may amplify this effect.

The first is reduced ecological corrective pressure for many beliefs. In digital contexts, many models can persist without contact with hard consequences. Feedback is often delayed, ambiguous, or socially mediated rather than grounded in physical outcomes. The second is miscalibrated trust weighting. Social prestige, emotional resonance, and group alignment can act as proxies for credibility, shifting meme trust calibration away from payoff tracking.

These observations should be stated as hypotheses rather than conclusions. The essay can propose a testable prediction: environments that decouple social information from reliable corrective feedback should increase the prevalence of behavior guiding cognitions that do not improve objective performance on ecologically grounded tasks, and they should reduce realized meme utility even when exposure is high.

Finally, the framework has an obvious bridge to artificial systems. Any learning system that ingests large volumes of socially produced information faces the same distinction between accessibility and utility. A system with high representational freedom can generate internal structure that improves performance, but it can also generate internally consistent structure that does not generalize or does not improve outcomes. The terms meme utility and cognitive noise can therefore function as conceptual tools for thinking about how artificial agents should gate social information, calibrate trust, and maintain strong corrective pressure during learning.

15. Conclusion

This essay has developed a neuroecological return on investment account of cognition organized around two constructs introduced in Reser (2006): meme utility and cognitive noise. Meme utility names the survival advantage conferred by acquiring and using socially transmitted behavioral information. Cognitive noise names cognition that influences future behavior without survival advantage. The central theoretical move is to treat cognition not as an unconditional benefit, but as a balance sheet with yield, noise, and overhead. Meme utility is positioned as a major input to cognitive yield because it supplies externally vetted behavioral priors that make cognition pay and reduce drift.

The framework generates a compact set of testable claims. Realized meme utility depends on acquisition, retention, applicability detection, and execution. Cognitive noise should expand when representational freedom is high but constraint and correction are weak, whether due to low parental scaffolding, low fidelity transmission, poor trust calibration, or low ecological corrective pressure. Precocial species can still exhibit cognitive noise, but the dominant sources and buffering mechanisms differ, with instinct reserve limiting the damage of miscalibrated internal models.

The broader contribution is conceptual. Meme utility and cognitive noise provide a language for connecting life history, parental investment, social learning, and the ecological profitability of cognition within a single, operationally tractable landscape. In that landscape, cognition is profitable when it is disciplined by reliable cultural constraint and strong corrective feedback. It becomes wasteful when it is forced to free run in the absence of those stabilizing forces.

Jared Edward Reser Ph.D. with ChatGPT 5.2

References

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the Evolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press.

Caro, T. M., & Hauser, M. D. (1992). Is there teaching in nonhuman animals? The Quarterly Review of Biology, 67(2), 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1086/417553

Csibra, G., & Gergely, G. (2009). Natural pedagogy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.005

Csibra, G., & Gergely, G. (2011). Natural pedagogy as evolutionary adaptation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1567), 1149–1157. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0319

Gould, S. J., & Lewontin, R. C. (1979). The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: A critique of the adaptationist programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 205(1161), 581–598.

Henrich, J. (2015). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press.

Henrich, J., Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2008). Five misunderstandings about cultural evolution. Human Nature, 19(2), 119–137.

Hoppitt, W., & Laland, K. N. (2013). Social Learning: An Introduction to Mechanisms, Methods, and Models. Princeton University Press.

Kurzban, R., Duckworth, A., Kable, J. W., & Myers, J. (2013). An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(6), 661–679. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12003196

Mercier, H., & Sperber, D. (2011). Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(2), 57–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000968

Neill, W. T., & Westberry, R. L. (1987). Selective attention and the suppression of cognitive noise. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13(2), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.13.2.327

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

Shenhav, A., Botvinick, M. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2013). The expected value of control: An integrative theory of anterior cingulate cortex function. Neuron, 79(2), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.007

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2006). The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 946–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

Sperber, D. (1996). Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Blackwell.

Sperber, D., Clément, F., Heintz, C., Mascaro, O., Mercier, H., Origgi, G., & Wilson, D. (2010). Epistemic vigilance. Mind & Language, 25(4), 359–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01394.x

Staal, M. A. (2004). Stress, Cognition, and Human Performance: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework (NASA/TM—2004–212824). National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Whiten, A., Goodall, J., McGrew, W. C., Nishida, T., Reynolds, V., Sugiyama, Y., Tutin, C. E. G., Wrangham, R. W., & Boesch, C. (1999). Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature, 399, 682–685.